I was raised in a primarily white community in Southern California. Instead of feeling proud of being Chinese American, all I wished was for my hair to be lighter, my eyes rounder, my skin a slightly pinker shade.

I grew up feeling out of place. I tried to blend in as much as possible through clothing, music and food choices. But still I would be reminded that I was “an other.” Kids would pull their eyelids back with their fingers and make sounds they thought mimicked the Chinese language. A student told me to go back to where I came from. I deflected idiotic questions ― why I didn’t have an accent, why my family ate with chopsticks ― by shrugging instead of challenging the askers. These microaggressions chipped away at me, forming the foundation of how I viewed myself.

So when I started at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where most of the 18,000 students had come from other places, the diversity felt like a different world. Groups of young Asian adults congregated in front of the student convenience store and walked to classes together. At home in northern San Diego, there was rarely more than one Asian in a room. Here, the Asian students seemed to revel in being together.

In my second year of college, a roommate asked me to pledge an Asian American sorority with her. In the early 1980s, independent Greek fraternal organizations were being created by minority students, mostly Asian and Latino, modeled after the African American organizations founded much earlier. Established in 1989, Chi Delta Theta was the first Asian American interest sorority at the university. Its focus was on bonding among sisters, performing community service and educating the public and one another about our cultural differences.

I had never thought of joining a sorority. After all, I already had friends. But because I had been curious about learning more about Asian culture and meeting more Asian Americans, I attended pledge week and found immediate connections with a number of the women in the sorority. Our conversations didn’t have that extra distance of having to wonder whether someone was judging or stereotyping me because of my ethnicity.

Ultimately it was an experience that exposed me to people and experiences I had missed while growing up. I found a community of other first- and second-generation Asian Americans, some of whom also had parents who had trouble speaking English. Some students had grown up in gang-ridden neighborhoods; some were pre-med, often nudged along by their successful parents. Despite our varied backgrounds, we found similarities through our personal experiences of having an Asian heritage.

My white friends didn’t have the same experiences, and they weren’t able to understand the pressure I felt when my mother wrote me emails lecturing me about my dating life, cajoling me to come home for Chinese holidays or pushing me to be a lawyer when I really wanted to major in art history. But my sorority sisters understood.

For social and charity events, we made the foods we missed from our homes and that represented our cultures, like fried rice, dumplings, lumpia and egg rolls, and noodle dishes. We celebrated Chinese New Year and Asian American Heritage Month. We never missed a Polynesian dance group performance.

But we also drank from beer bongs, had barbecues at the beach and ate Jack in the Box tacos after a night of partying, like every other college student. Joining the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Greek system exposed me to the wonderful blend of being Asian and being an American at the same time. Where my childhood had been spent hiding the fact that I was different, joining the sorority allowed me to celebrate being Asian, something I could not have imagined as a child.

As a result of joining the sorority, I became more active in the broader Asian American community on campus. With two women who were not part of the Greek system, I co-founded the Asian Student Union and was recognized by the NAACP’s local chapter. I also took my first Asian American studies class and learned more about the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and the 1982 racist murder of Vincent Chin in Michigan, topics that weren’t discussed in my high school history classes.

After college, I returned to San Diego to attend law school, where my activism and diverse group of friends declined. Focused on succeeding in the legal field, I didn’t join any Asian interest organizations. As with many college graduates, I still remembered my time in college as one of the favorite periods of my life. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that this was the only time when I had overtly celebrated being Asian.

In 2021, given the rise in violence against Asians during the coronavirus pandemic, I took my family to a protest against AAPI hate. My husband, who isn’t Asian, asked why I suddenly wanted to protest. I explained that “Asians typically don’t speak up because we don’t like to rock the boat. But what’s going on is unacceptable, and if we don’t speak up, no one will speak up for us.”

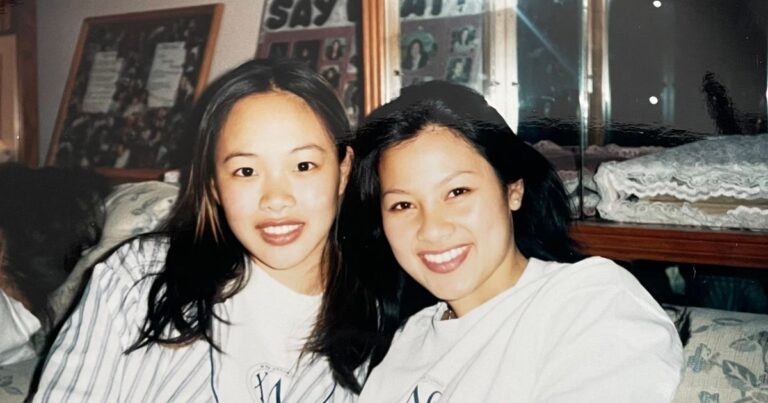

Courtesy Of Joanne Saunders

The next day, my kids and husband held signs as we walked with hundreds of people down the Pacific Coast Highway as supporters honked and waved from their cars. We listened to the college student organizers talk about how much we needed to support one another ― more today than ever before. We were together not to celebrate being Asian but to tell the world we have suffered, too.

Since then, I’ve been looking into organizations that support anti-racism, social justice and the environment, all interrelated issues. I’ve rediscovered the importance of education, but it’s not just about educating me this time. It’s about educating the public and my children.

A couple of weeks ago, my son told me another student called him a derogatory name in reference to his Asian appearance. It hurt to know that our society hasn’t come that far since I was a child. Maybe my middle school son will one day join an Asian American interest fraternity to find comfort and pride that AAPI Greek life gave me. In the meantime, I will tell him what I learned there: that we are just as American as everyone else, and we must celebrate our Asian heritage, not resent it.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.