There are a lot of factors that drive the performance of financial markets over time.

Fundamentals like valuations, economic growth, earnings and dividends are the main drivers of returns over the long run. Plus you have to consider demographics, productivity and innovation. And the hardest variable to quantify will always be psychology. No one can predict how people are going to feel in the future.

There is another element you won’t find in the finance textbooks that becomes more obvious the longer I work in the wealth management business — barriers to entry.

It was much harder to invest in the stock market in the past so it was mostly wealthy households who did so. And it wasn’t just the market itself that was difficult to access — there were also barriers to information.

People in the past simply didn’t have the data or knowledge about the long-term benefits of investing in the stock market.

Add it all up and we should see ever-rising allocations to stocks over time.

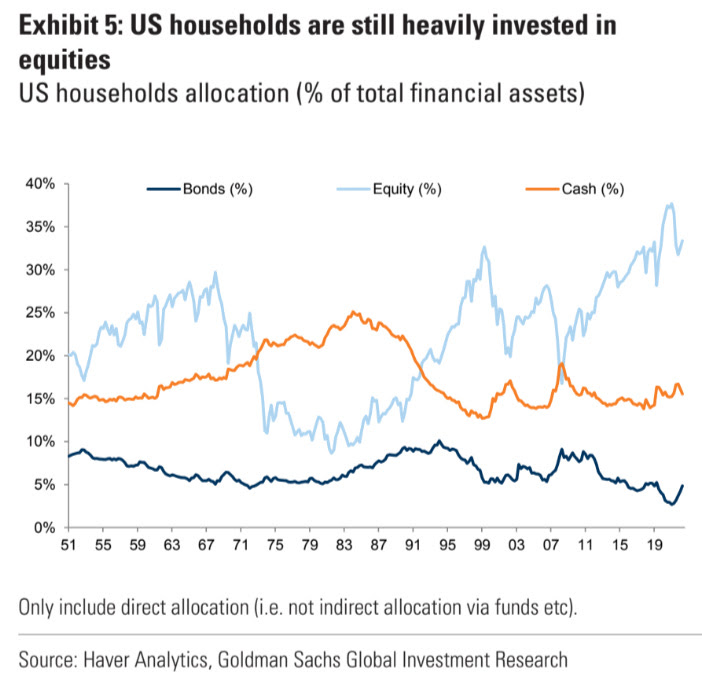

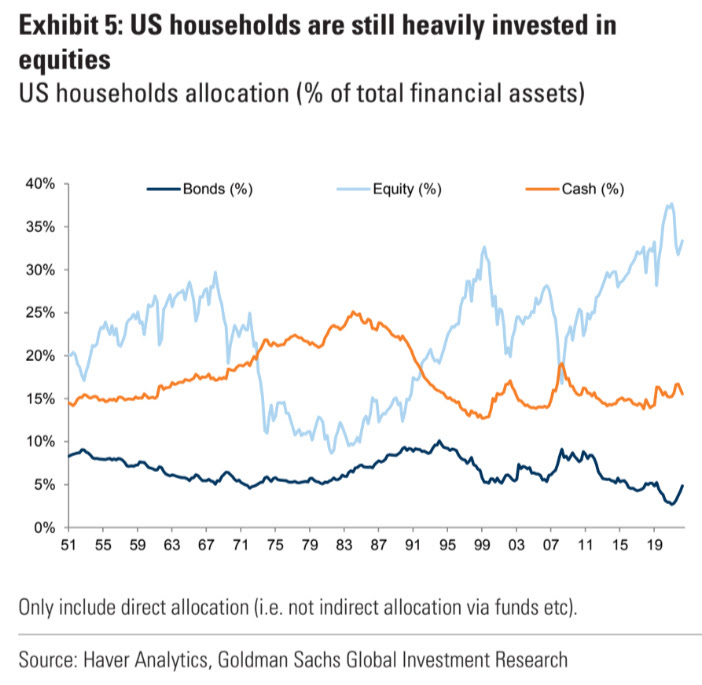

Just look at this chart from Goldman Sachs on the changing nature of allocations to stocks, bonds and cash since the 1950s:

Household allocations to the stock market have been volatile much like the stock market itself but there has been an upward trend since the 1970s. I would expect the elevated allocation to equities to continue into the future.

Why?

Most people in the past either didn’t invest in the stock market or didn’t have the ease of access investors do today when it comes to gaining exposure to the greatest wealth-building machine on the planet.

Sure, stock market allocations were higher in the 1950s and 1960s than they were in the 1970s but those numbers are deceiving. Most people simply didn’t invest their money in those days, especially in the stock market.

In 1953 only 4% of the country owned stocks. Even after the 1950s bull market that saw the U.S. stock market rise by nearly 500% (19.5% per year for a decade) there were only 12.5 million stockholders out of a population of 177 million. That’s 7% of the total.

The stock market was more or less a curiosity to most people until the 1980s.

Inflation in the 1970s didn’t help. By the end of that decade you not only had stocks perform poorly but savers could get double-digit yields on their cash in money markets, CDs and savings accounts.

Why would you want to invest in stocks when you could earn 15% in with no market risk?

Fidelity burst onto the fund scene in a big way in the 1960s as mutual funds became the new preferred way to invest in stocks. The fund firm estimates they had nearly $5 billion in assets in 1968 and 90% of it was in stocks. By 1982, they were managing $17 billion but only 12% of assets were in stocks.

The death of equities wouldn’t last though.

Not only did interest rates and inflation peak in the early-1980s, but a tax bill in 1981 contained a provision that allowed workers to lower their taxable income by $2,000 by putting it into a new tax-deferred retirement.

The IRA was born, and all that cash on the sidelines had a new home that allowed people to invest in the stock market in a tax-deferred investment vehicle.

Fidelity was opening up 10,000 new accounts a day in the lead-up to the 1983 tax deadline. T. Rowe Price said 70% of incoming IRA money was going into stock funds in 1983 versus just 28% in 1982. Merrill Lynch said customers who opened accounts to invest in stocks doubled once IRAs became available.

IRAs not only gave people an incentive to save for retirement but also forced them to realize they were on their own when it came to saving for their post-work years.

Joe Nocera highlighted this sea change in his book A Piece of the Action:

The 10 million households with money market funds represented merely the first wave of prospective IRA customers. Every employed person in the middle class was a potential customer. At the time the new IRA rules went into effect, there were 36.5 million households with incomes of $20,000 or more. “This figure,” wrote the ICI research department in an enthusiastic missive to its members, “translates to around 50 million individuals who are potential IRA purchasers. The IRA potential,” the trade group exhorted its members, “is tremendous.” Robert Metz, a financial writer for The New York Times, estimated that potential at around $50 billion. He wasn’t even close; by 1992, IRA accounts held $724 billion.

Mimi Lieber, a consultant to the financial services industry, conducted a number of studies on IRAs and became convinced that IRAs were truly the financial device that brought home the realization that the American middle class was going to have to take control of its own financial future. “It was the first real incentive for a great number of Americans to put money away for the long term,” she says now. “And these were generally people who up until then hadn’t seen themselves as having any control over the long term.” It was a device that made people feel both empowered and burdened, her studies showed. As much even as inflation, it caused people to begin learning what they could do with their money.

By 1987, 55 million people had opened a mutual fund account and most of those funds were invested in stocks. The 1980s bull market was the first one in history to include younger investors and the middle class.1

The addition of low-cost brokerages and 401k accounts also played a role here. Now that investors have broader access to index funds, targetdate funds and automated investing tools, it’s no wonder equity allocations have been rising over the past 5 decades.

This stuff matters when looking at historical relationships and averages for the stock market.

The addition of retirement accounts and automated contributions was a game-changer for financial markets.

I’m not saying this makes historical fundamentals in the stock market meaningless but it does mean context is required when comparing now and then.

Further Reading:

The Evolution of Financial Advice

1In Nocera’s book Peter Lynch thought the Cold War kept most people out of the bull market of the 1950s and 1960s. He said the country was more obsessed with building bomb shelters than investing for the future. That might be true but I think the barriers to entry probably played a bigger role here.