In late-2019, The Economist put out a 150 page report called The World in 2020 that offered some predictions for the coming year in geopolitics and the economy.

The issue was full of thoughts and ideas from CEOs, economists, scientists, politicians and business leaders about what was coming in the year ahead.

These thought leaders were worried about the lasting impacts of Brexit, the upcoming U.S. presidential election, China’s role as a global superpower, climate change and more. They weren’t worried too much about a recession or a stock market crash or anything related to a healthcare panic.

Obviously, no one knew how badly the Covid epidemic would disrupt life as we knew it heading into 2020.

How could anyone possibly predict what was coming?

To their credit, The Economist issued a mea culpa in a follow-up at the end of 2020:

Well, we didn’t see that coming. Like almost everyone else, we were blindsided by the outbreak of covid-19, the first cases of which were identified in December 2019. As well as causign death and hardship around the world, and the delay or cancellation of events large and small, one of the pandemic’s less important side-effects was to invalidate most predictions for 2020, including our own.

We expected a global slowdown, but not the biggest economic contraction since the Depression. We anticipated continuing Sino-American tentions over Chinese exports, but not of the viral variety. We looked forward to action to reduce greenhouse gsa emissions, but not an 8% annual reduction, the largest since the second world war, as the pandemic throttled transport and industrial activity.

The pandemic truly changed the trajectory of the world forever.

No one could have predicted what would happen or the potential ramifications from how we live to where we work to the prices we pay to where people live to the wages people earn and on and on down the line.

But that’s the point.

We didn’t see that coming should be your default assumption when it comes to risk assessment. The risks aren’t always going to be as big as a pandemic but things rarely follow the script when it comes to how people assume things will work out.

When “everyone” does feel certain about the way things are going to work out, it usually doesn’t happen that way. This headline from October 2022 is a perfect example:

We’re still waiting on that recession. Any day now.

Here’s a more recent article from one year later:

This story was plus or minus a day or so from the peak in yields. The 10 year Treasury topped out at 5% in October; it’s now below 4%.

We humans are bad at forecasting the future because of recent bias, availability bias and overconfidence. But it’s also true that predicting the future is impossible because so much of what happens is impossible to predict since the world is inherently unpredictable.

This is true of both short-term forecasts and long-term forecasts.

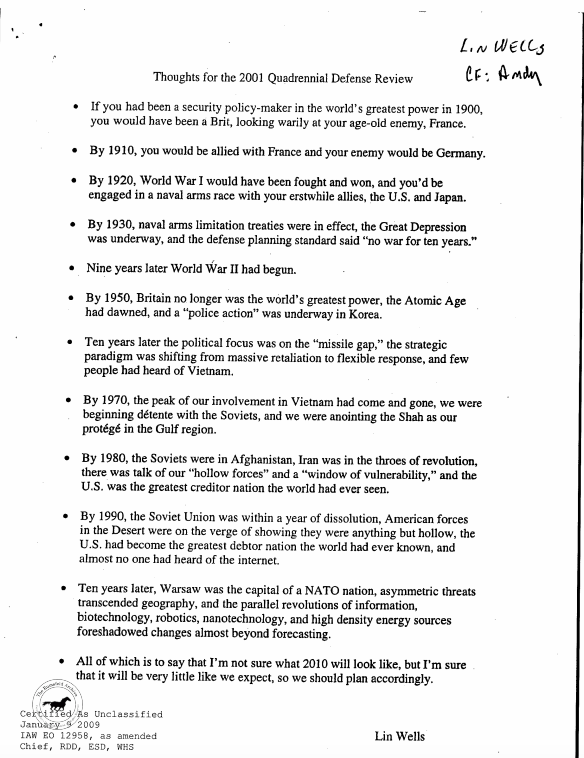

Lin Wells worked at the Pentagon for both the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations. Wells drafted the following document for Bush in April 2001:

The kicker here is my favorite part of the memo:

All of which is to say that I’m not sure what 2010 will look like, but I’m sure that it will be very little like we expect, so we should plan accordingly.

Less than six months later came 9/11. The first decade of this century included two wars, two gigantic stock market crashes, a housing bubble (and bust), a mild recession and the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Wells was right — no one had a clue how things would look in 2010 back in 2001.

I have some thoughts on things that could happen in 2024 but there is a good chance those thoughts will be proven useless because something unexpected will change things up.

The stock market could be up or down depending on interest rates, the inflation rate, economic growth, earnings, investor sentiment or something else completely out of left field.

The next big risk is rarely the one everyone is talking about or planning ahead for.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t make forecasts. Everyone essentially needs to make forecasts about the future to survive.

Companies need to make forecasts to plan for the future to figure out their investments, outlays and hiring decisions.

Households need to make forecasts to plan out their spending, borrowing and consumption patterns.

Investors need to make forecasts to set baseline expectations of gains or losses for financial planning purposes.

People who go on vacation need to look at the weather forecast so they know what to pack for the trip.

Forecasting is fine. Everyone has to think about the future, whether they like it or not.

But it’s important to understand how often life gets in the way of your expectations. Surprises occur more often than anyone could imagine.

Something surprising will happen in 2024.

Just don’t be surprised that you’re surprised when it does.

Further Reading:

No One Knows What Will Happen