As millennials reach middle age (hand up), prepare yourself for a wave of 1990s nostalgia.

Remember MTV? Remember life before smartphones and social media? Remember rap groups? Remember life before everyone was forced to care about politics? Remember Saved by the Bell? Remember going to Blockbuster on a Friday night to pick out a movie?

Finance people also have an affinity for the 1990s economy. Remember how great things were?

What if the 1990s economy is already back in style?

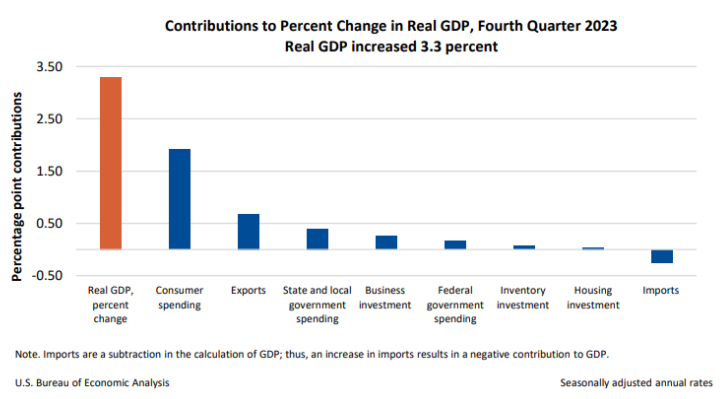

The economy just grew at a real rate of 3.3% in the fourth quarter following 4.9% annualized real growth in Q3:

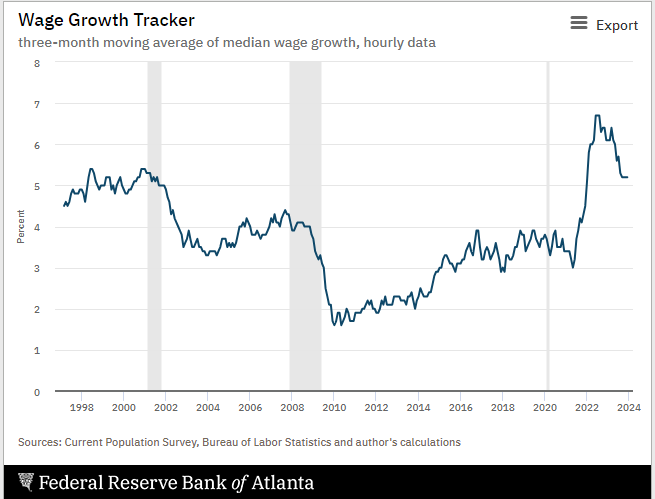

Wages are growing at more than 5%:

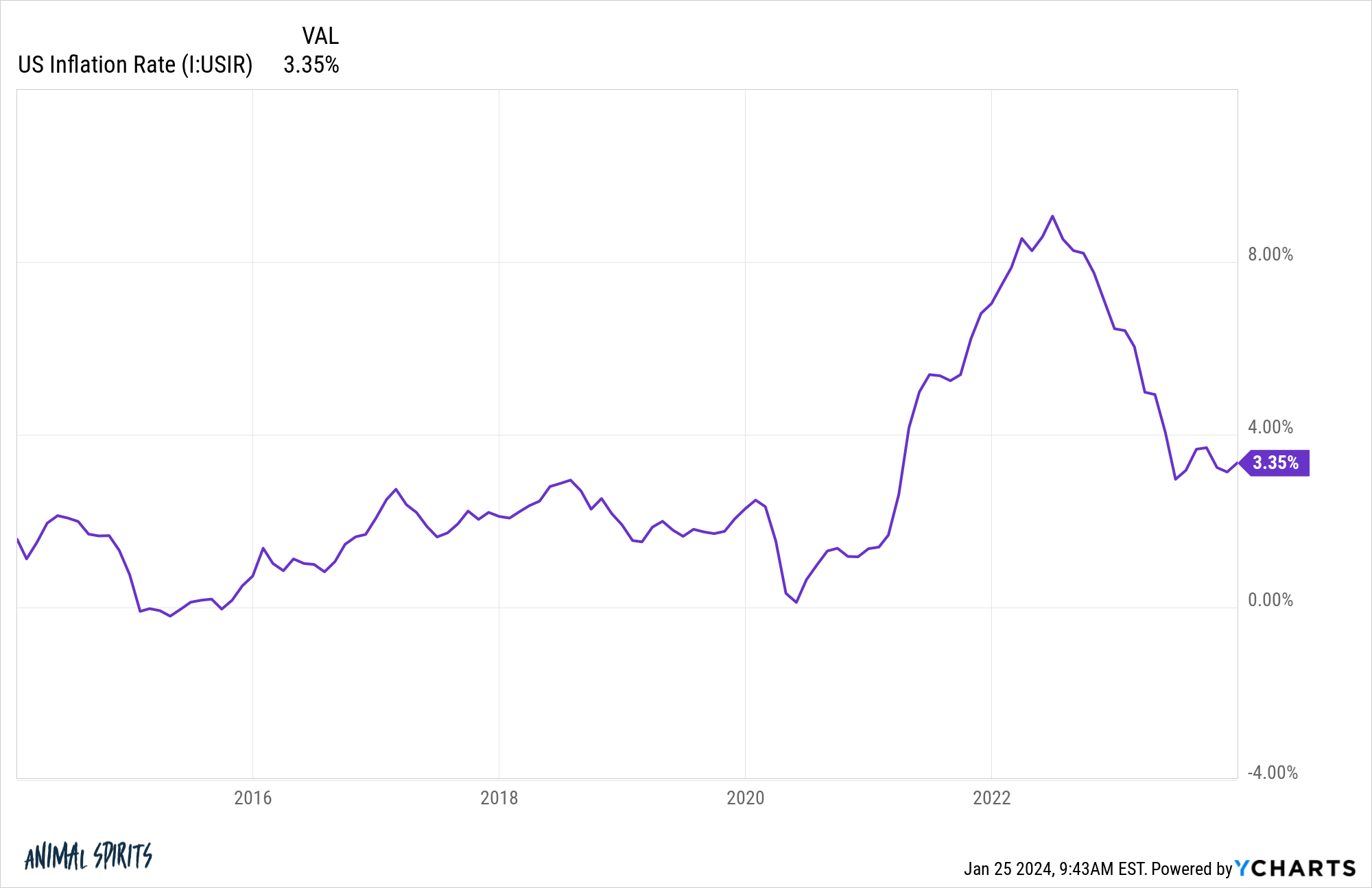

And inflation is around 3%:

So we’re talking 2% real wage growth and 6% nominal economic growth. People were worried about a repeat of the 1970s. The current environment looks more like the 1990s economy than the 1970s.

Obviously, there are plenty of differences between the current environment and the 1990s boom times. Some bad, some good.

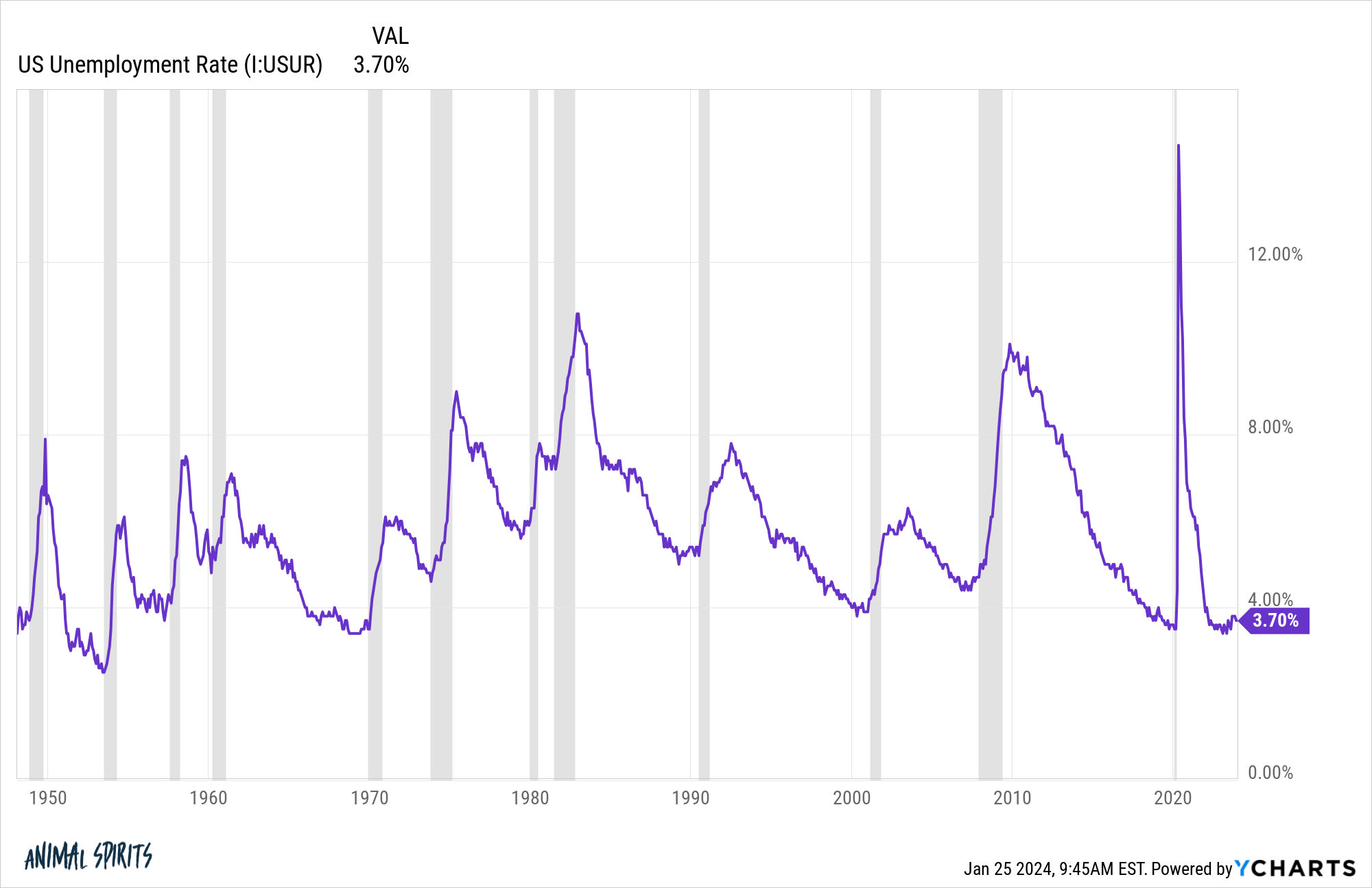

The unemployment rate is still below 4%, a level it never breached in the 1990s:

The unemployment rate averaged nearly 6% in the 1990s. It closed out the decade right at 4% but never went below that level in the decade.

Government debt is a lot higher now than it was back then. $34 trillion is a lot of money.

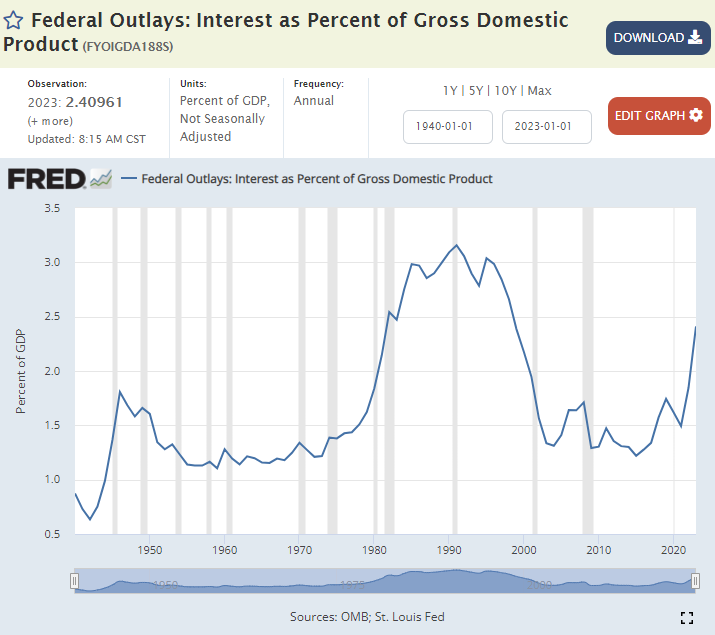

But look at interest expense as a percentage of GDP:

It’s rising at a fast clip because the Fed raised interest rates, but it was much higher in the 1990s. We need to get our spending under control at some point but this is not the crisis some people would have you believe.

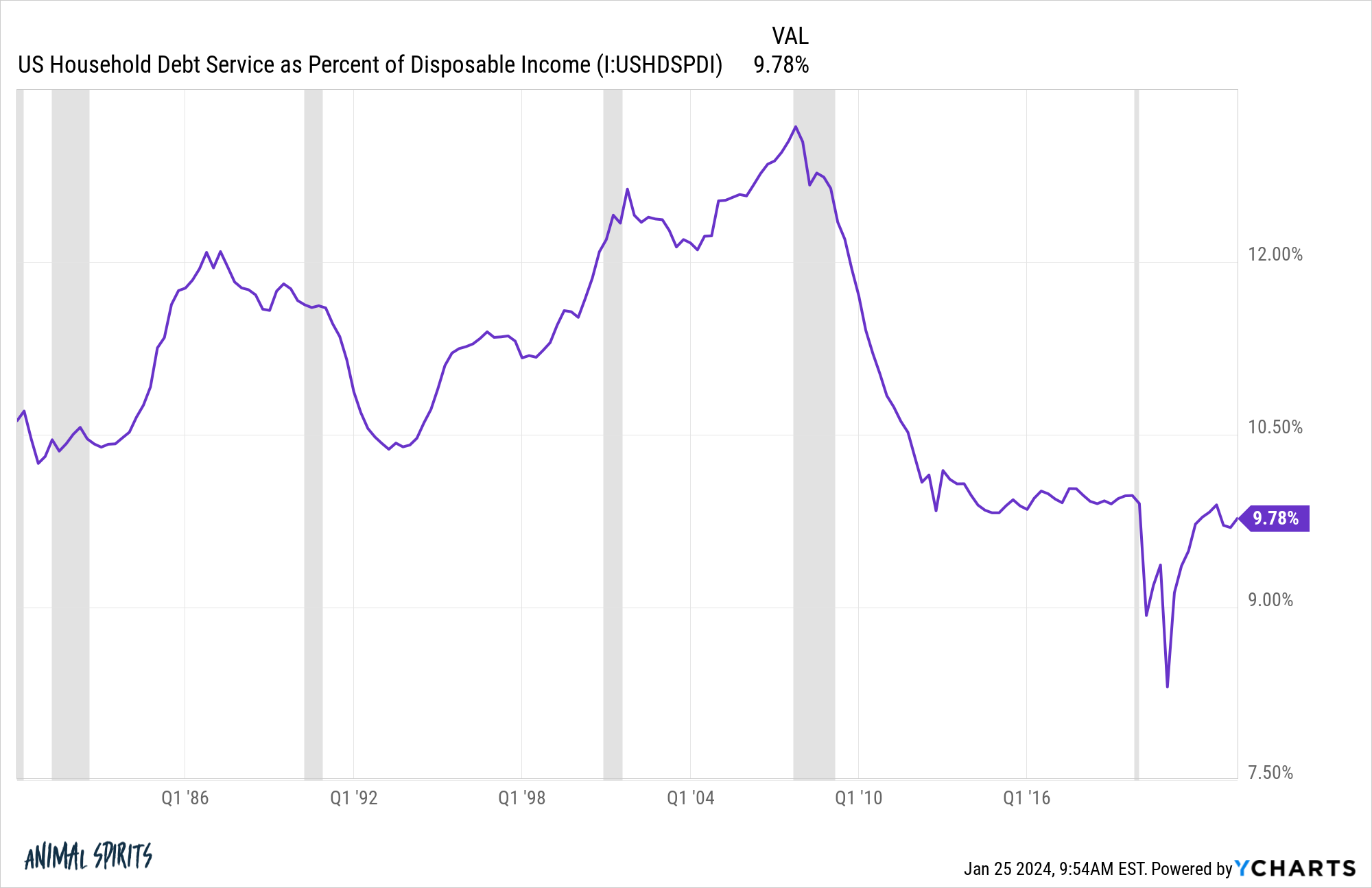

A similar picture emerges when you look at consumer debt levels:

Consumer balance sheets are in a much better place now than they were in the 1990s when it comes to debt levels.

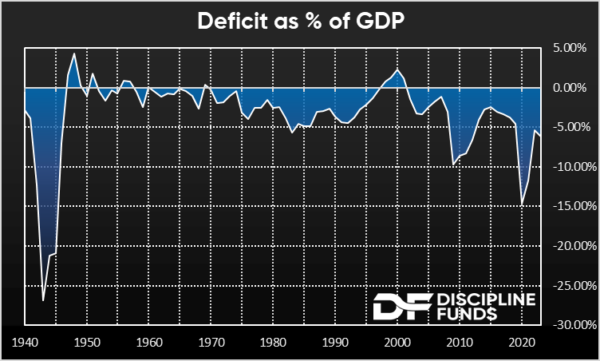

What about the deficit?

It blew out during the pandemic, of course, but it’s now back to levels that are closing in on what we saw in the 1990s (chart via Cullen Roche):

The biggest difference between now and the 1990s is we had far better music and movies back then. The 1990s are to Gen X and older millennials as the 1960s are to baby boomers. Luckily, we have better TV shows today and the ability to watch them on giant HD TVs.

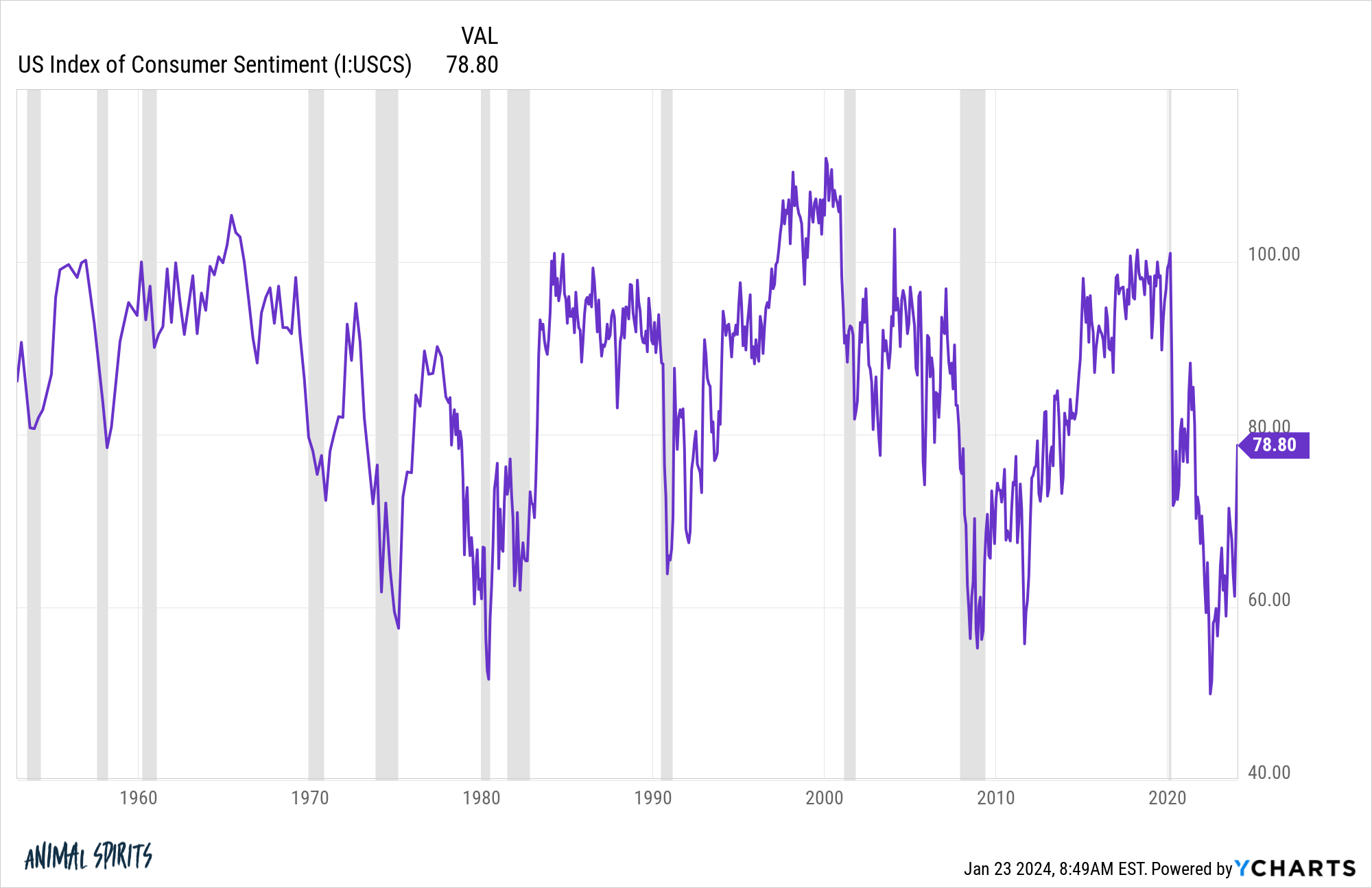

The second biggest difference between now and the 1990s is probably sentiment:

People were euphoric in the 1990s.

Sentiment numbers have rebounded in recent months, but it’s wild to see numbers in 2022 lower than the Great Financial Crisis or the 1970s.1

Obviously, this situation won’t last forever. As Brian Flanagan once so eloquently put it: “Everything ends badly otherwise it wouldn’t end.”

The current economic expansion will end badly. The economy will slow. We will have a recession at some point.

In fact, the labor market is already beginning to slow. The Wall Street Journal had a story this week about the difficulty some job seekers are now having in finding a new role:

Those who are actually job hunting–versus those who might be venting their work frustrations–are discovering that they have less leverage than in the recent past. Companies are offering new hires less-generous pay and flexibility than they did a year or two ago, data from job boards suggest. They are also holding the line in negotiations over perks such as additional vacation time, applicants say.

On LinkedIn, one job opening is available for every two applicants. A year ago, jobs outnumbered applicants two to one.

“The pendulum has swung back, and the power is in the hands of the hiring managers,” says Catherine Fisher, a LinkedIn vice president who tracks job trends.

This might be good news for the Fed in terms of inflation, but it’s bad news for workers. As always, there is give and take with these things.

The good news is the Fed has some room to lower interest rates should the labor market cool off considerably.

The strange thing about the prospect of Fed rate cuts is the stock market is at all-time highs.

Usually, the Fed is cutting rates when the stock market is getting wrecked.

The last time the Fed cut rates was during the pandemic when the world was falling apart. They also cut in 2018 when we had a mini-bear market towards the end of the year. Before that the Fed cut rates to 0% during the Great Financial Crisis.

This time around the Fed was raising rates as the stock market was crashing and now they’re likely going to lower them after stocks have recovered.

The last time the Fed was cutting interest rates during a time when the stock market was charging higher was, you guessed it, the 1990s.

Alan Greenspan and company were slowing but surely raising rates in the latter half of the 1990s but then Russia defaulted on its debt in 1998, leading to an emerging markets crisis and the Long-Term Capital Management disaster. Plus, people were worried about Y2K for some reason so the Fed cut rates.

In 1999, GDP growth was more than 4%, the unemployment rate was 4% and inflation was less than 3%. Yet the Fed briefly cut interest rates.

That was a different environment in many ways, but it certainly helped propel the stock market to blow off top levels in the dot-com bubble.

I don’t know what’s going to happen if the Fed cuts interest rates this year but neither does anyone else.

As much as the current economic backdrop is giving me 1990s nostalgia, there is no crisis to speak of right now. There is no real precedent in recent history we can point to.

It will be curious to see if the Fed can cut rates to a level that keeps the economic machine chugging along though.

Hopefully the economy is entering 1995 instead of 1999.

Michael and I talked about the economy, the Fed cutting rates, all-time highs in stocks and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Americans Have Never Been Wealthier & No One is Happy

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

Books:

1Spoiler alert: 2022 was not worse than 2008 or the 1970s. Not even close. Another difference between now and then is how politicized everything is, including sentiment numbers which are being skewed by political beliefs in a way we’ve never seen before. See here.