I’m really late on this one, but I finally got around to reading Andre Agassi’s autobiography.1

He writes about what it was like to finally win his first Grand Slam tournament at Wimbledon. Everyone’s perception of Agassi changed from choke artist to the real deal.

Winning, however, didn’t change how he felt about himself:

But I don’t feel that Wimbledon has changed me. I feel, in fact, as if I’ve been let in on a dirty little secret: winning changes nothing. Now that I’ve won a slam, I know something that very few people on earth are permitted to know. A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close.

This secret is true in sports and many other facets of life.

I’ve talked to my oldest daughter about this lesson many times. Over the past couple of years, she’s become a rabid sports fan.

Anytime her teams lose it’s so much more painful than the good feelings she gets when her teams win.

Everyone knows this feeling. It’s human nature.2

I didn’t realize this inherent human quality had a name until I started reading Daniel Kahneman’s work.

Kahneman passed away this week. His understanding of the human condition was unparalleled.

Jason Zweig wrote a touching tribute to Kahneman that covers the importance of his ideas on how losses affect us:

No, Danny said, money lost isn’t the same as money gained. Losses are more than twice as painful as gains. He asked the conference attendees: If you’d lose $100 on a coin toss if it came up tails, how much would you have to win on heads before you’d take the bet? Most of us said $200 or more.

Kahneman’s loss aversion is perhaps the most important money concept of them all. Losses impact your money emotions in so many ways.

Losses can cause panic in the markets.

Losses can change your perception of risk.

Losses in the present can impact your investment posture in the future.

The fear of losses can cause investors to create suboptimal portfolio allocations.

Losses can force investors into holding onto losing positions because they won’t sell until they break even.

Inflation is a loss of purchasing power, which explains why it’s such an emotionally charged topic.

Losses are so painful you can relive them in your sleep.

The ability to deal with losses is what separates successful investors from unsuccessful investors. You’re in trouble if losses cause you to overreact or make big mistakes at the worst possible moments.

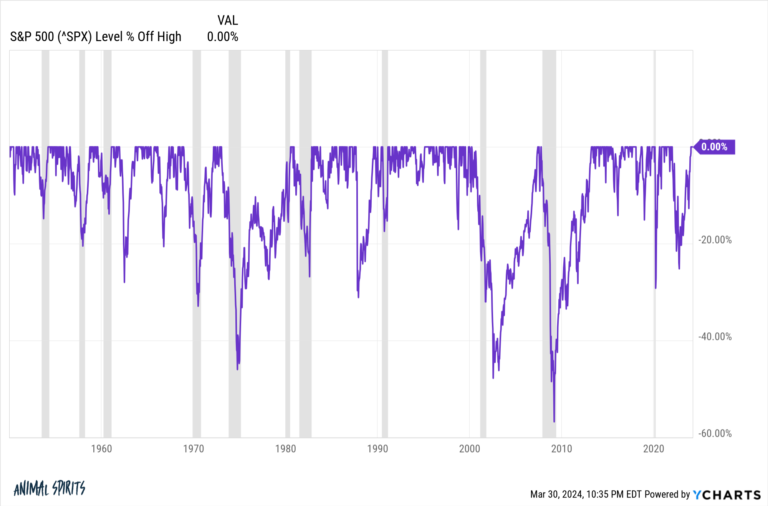

You cannot make it in the stock market if you don’t have the ability to deal with losses on occasion. I can’t guarantee what future returns will be in the stock market. I can guarantee there will be teeth-rattling losses at some point.

Perhaps the most important way to deal with this bias is to recognize how loss aversion can impact your feelings and reactions.

After retiring from late-night television, David Letterman talked about what it was like to compete with other late-night hosts his whole career:

“I think there’s something wrong with me,” he said, only half joking. “It’s either a character flaw or a personality disorder. It’s one or the other. I haven’t heard back from the lab.”

More earnestly, he added: “Maybe life is the hard way, I don’t know. When the show was great, it was never as enjoyable as the misery of the show being bad. Is that human nature?”

Yes, Dave, that’s human nature.

Everyone has their own character flaw or personality disorder when it comes to money emotions.

Managing those emotions is even more important than how you manage your portfolio.

Further Reading:

Lessons From Thinking Fast and Slow

1The Agassi-Sampras era remains my favorite as a tennis fan.

2This a not-to-brag but my football team in high school made it to the state championship game my junior and senior seasons. We lost in the finals my junior year but came back to win it all my senior season.

Guess which game I still think about more? The loss! The missed opportunities from that game are replayed over in my mind far more often than the triumphs from the victory in the following year.

That loss still eats at me.