A reader asks:

Why is capping credit card rates a bad idea? What are other ways we could make rates less insane?

President Trump threw out an idea recently to cap credit card rates at 10%.

At face value, this sounds like a good idea.

Credit card rates for most borrowers are in the 20-30% range. The average balance for the 45% or so of people who don’t pay off their balance each month is around $6-7k. Carrying a balance while paying borrowing rates that high is a sure way to crush your finances and credit score.

So why would capping these rates be a bad idea?

JP Morgan CFO Jeremy Barnum explains it like this:

Our belief is that actions like this will have the exact opposite consequence to what the administration wants for consumers. Instead of lowering the price of credit, we’ll simply reduce the supply of credit, and that will be bad for everyone: consumers, the wider economy, and yes, at the margin, for us.

Basically capping rates would cause banks to pull back their lending in this space. Only those with solid credit scores would be able to borrow. Those who rely on credit cards to finance their lifestyle would be forced into payday loans or other more onerous borrowing schemes.

I don’t think capping credit card rates at 10% makes sense but I also don’t think the current system is fair for those who are stuck in debt that compounds against you faster than the best investors on the planet. It never made sense to me that credit card rates always remained high even when other borrowing rates were so low for much of the 2010s and early-2020s.

To understand why credit card rates are so high and how we got to this point it’s worth walking through a short history of credit cards with some help from Joe Nocera in his book A Piece of the Action, which chronicles the growth of consumerism in the latter half of the 20th century.

The first boom in consumer credit came during the Roaring 20s. The freewheeling attitude from that time got stamped out in a hurry by the Great Depression, which turned an entire generation of people into frugal misers.

People didn’t want to spend money again until the aftermath of WWII, when everyone wanted to borrow money to fund their middle-class lifestyle. People wanted to buy refrigerators, televisions, new homes, and the latest car model. And they didn’t want to wait.

Most banks weren’t equipped to handle this new consumer. There was no real differentiation in consumer financial institutions back then. No one paid interest on checking accounts and passbook savings account rates were governed by law. Most people just picked the most convenient bank nearest to their home or work.

Most banks were more focused on business loans than consumers. In fact, banks were hesitant to provide consumer credit because they wanted to protect households from the dangers of borrowing too much money.

Bank of America was the first financial institution to see the growing importance of consumers in the new economy. After witnessing massive growth in installment loans, they started testing out the BankAmericard in the late 1950s.

In 1958, Bank of America sent 60,000 credit cards to households in Fresno, CA. No one asked for them. They just arrived in the mailbox. By 1959, 2 million cards were in circulation and it was off to the races. Chase and American Express were right behind them with offerings of their own.

So how did they set the interest rates so high for these cards?

Joseph Williams was the architect of the BankAmericard. Williams set credit card interest rates by examining how companies such as Sears set theirs. Nocera explains:

Williams had friends at Sears and Mobil Oil, and those friends secretly allowed his team to observe their credit operations. Out of this latter research, incidentally, came a number of the standard features of credit cards, features that have remained remarkably unchanged to this day. The idea of a one-month grace period, a time during which customers could pay off their balances without facing interest charges, emerged from that research, as did the idea of charging 18 percent a year on credit card loans–a figure that would be seemingly set in stone for the next thirty years, even as every other manner of interest rate fluctuated wildly. There was no black magic involved: The bank just assumed that if a one-month grace period and a monthly interest charge of one and a half percent (which amounts to 18 percent a year) was good enough for Sears, with its fifty years of credit experience, then it was good enough for the Bank of America.

They also needed to get merchants on board to facilitate these new transactions.

That was an easy sale.

The bank would act as a de facto back office for retailers, guaranteeing the payment in a short period of time, collecting payment from the customers, and making the process simple and easy for the consumer to spend money. The initial cut was 6% of every transaction.

The initial rollout was a disaster.

Fraud was rampant. Too many people didn’t pay their balances on time. Fifteen months in, Bank of America had lost more than $20 million, a substantial sum in those days.

One of the reasons the high rates stuck after the rollout period is because far fewer people paid off the balance each month than anticipated. Delinquency rates exceeded 20% (they estimated it would be 4%).

So they cleaned things up, dropped users who failed to pay, added some penalties to the process and beefed up fraud prevention. By the end of the 1960s, credit cards were a new profit center for the bank.

The use of consumer credit exploded, going from just $2.6 billion in 1945 to $45 billion by 1960 and $105 billion in 1970.1

The rest is history.

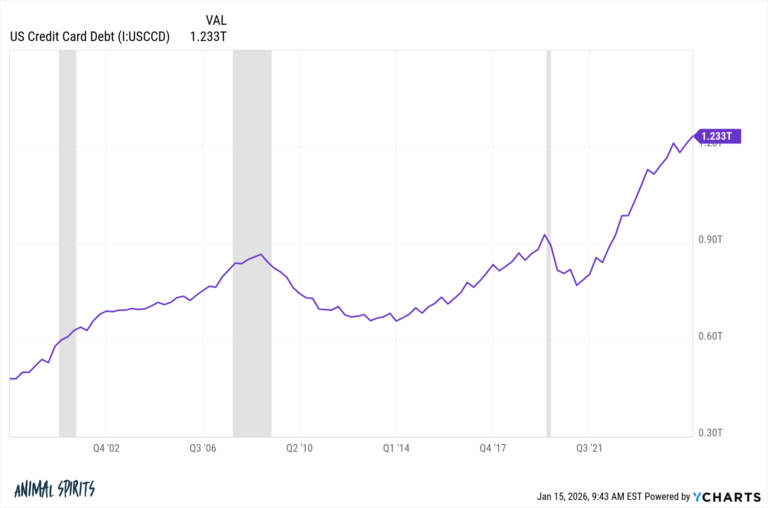

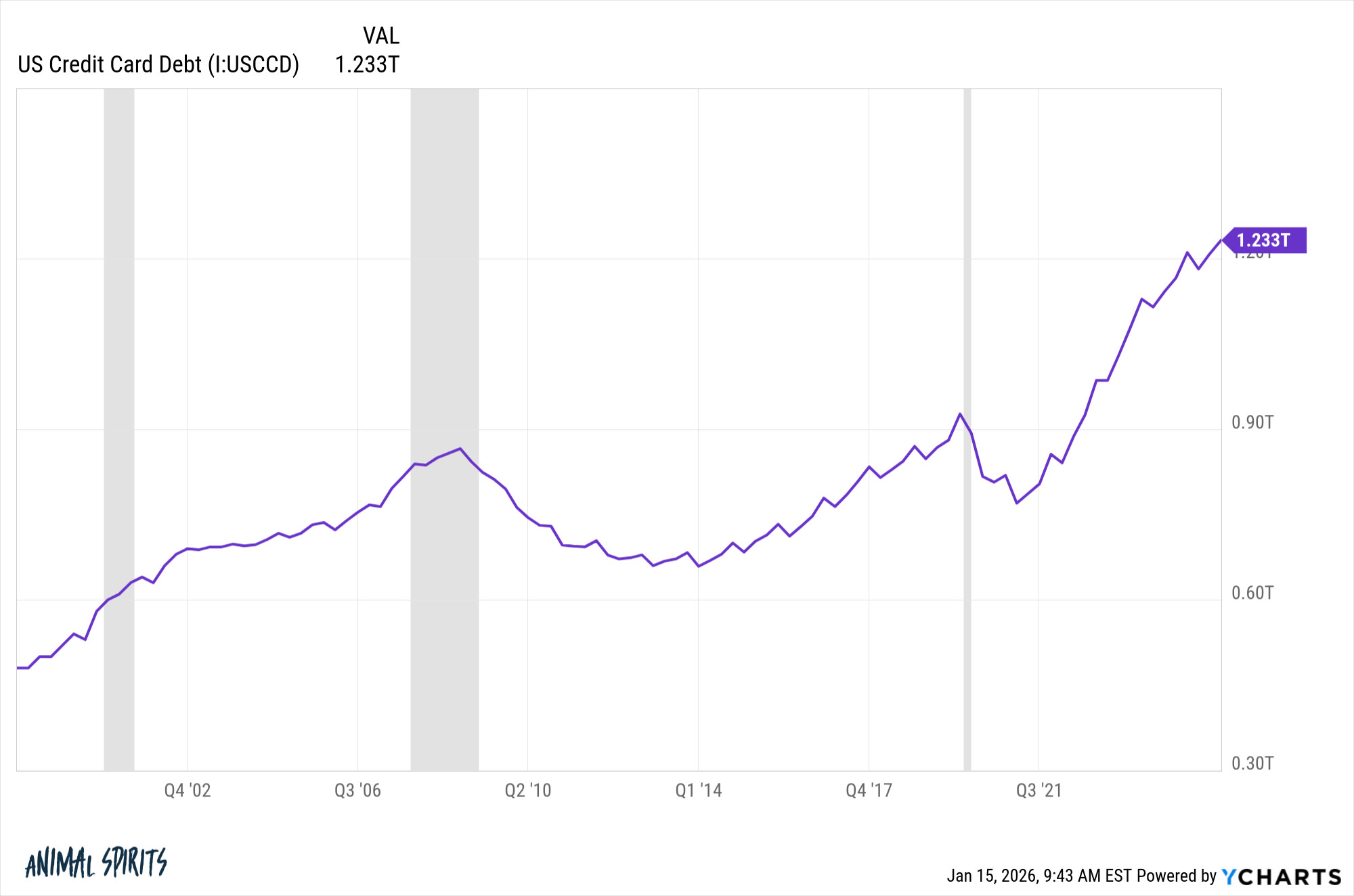

We now have more than $1.2 trillion in credit card debt in America:

Credit card rewards are a business in their own right, in which people who pay off their balances each month are effectively subsidized by those who don’t.

Last year alone, American Express paid Delta more than $8 billion for its credit card/mileage rewards partnership.

So the biggest reason there are such high rates and high fees on credit cards is because we’ve always done things this way. This is not the system you would design if starting from scratch today.

How do you help people who are struggling with the burden of credit card debt?

Financial education would help.

Right or wrong, the best way to lower rates on credit cards is likely more exacting credit standards. These loans aren’t backed by anything, which is another reason the rates are so high.

I don’t know that there is a systemwide solution you can wave a magic wand at to fix this.

If you have credit card debt, don’t rely on the government to fix it for you.

Negotiate with the credit card companies if you can’t repay the loans. You can try to negotiate the ridiculously high late fees as well. Or you can consolidate to a lower rate.

But carrying a balance is one of the worst financial decisions you can make. Rates are so high that it’s a negative compounding effect.

Barry Ritholtz joined me on Ask the Compound this week to tackle this question in detail:

We also answered questions about stock market valuations, 401k contributions, the best sources of financial information and buying vs. renting.

Further Reading:

How Bad is Credit Card Usage in America?

1In the 1950s Bank of America had a $60 million loan portfolio made up almost exclusively of $200 refridgerator loans.