In a rational world every investor would set their asset allocation based on their willingness, ability and need to take risk.

One would balance a range of expectations for the various asset classes and match those possibilities with their goals and objectives.

Sure, plenty of investors consider their risk profile and time horizon when building a portfolio.

But we live in an irrational world — one in which experiences, emotions, circumstances, luck and timing shape both feelings and portfolios.

The Economist recently had an excellent profile on how young people should think about investing and why they shouldn’t freak out because of the inflationary bear market of 2022.

They point to research from Vanguard that shows your early experience in the markets can shape your asset allocation and investment posture for years to come:

Ordering the portfolios of Vanguard’s retail investors by the year their accounts were opened, his team has calculated the median equity allocation for each vintage (see chart 3). The results show that investors who opened accounts during a boom retain significantly higher equity allocations even decades later. The median investor who started out in 1999, as the dotcom bubble swelled, still held 86% of their portfolio in stocks in 2022. For those who began in 2004, when memories of the bubble bursting were still fresh, the equivalent figure was just 72%.

Therefore it is very possible today’s young investors are choosing strategies they will follow for decades to come.

This is the aforementioned chart:

These results are somewhat surprising. Most people assume living through the inevitable bust that follows a boom would leave a sour taste in your mouth.

But the opposite is true. Investors who opened accounts during boom times actually retained a higher allocation to stocks for years to come.

Maybe it’s inertia but it’s obvious stock market returns in your formative years as an investor can have an impact on how you invest.

The hard part about all of this is you don’t get to choose when your returns come as an investor. Sometimes you get good returns when you’re young, sometimes when you’re old.

Some retirees get fabulous bull markets right when they leave the working world while some retire into the teeth of a bear market.

Timing and luck — both good and bad — play a huge role in your experience as an investor.

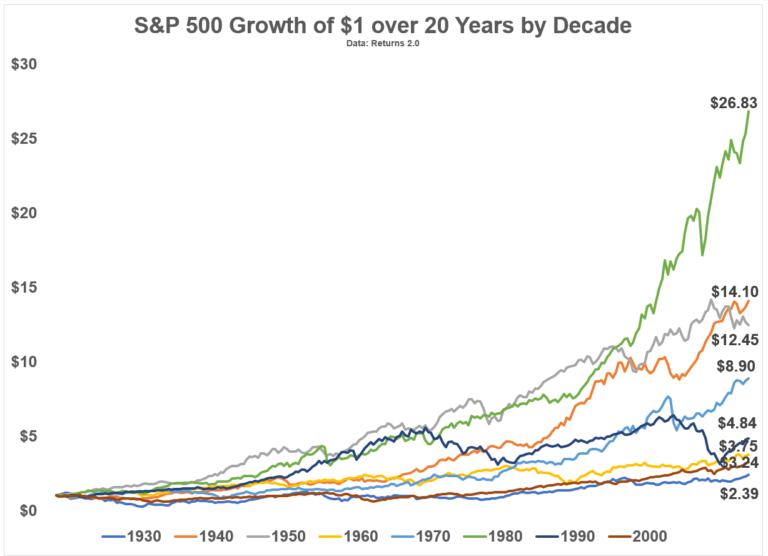

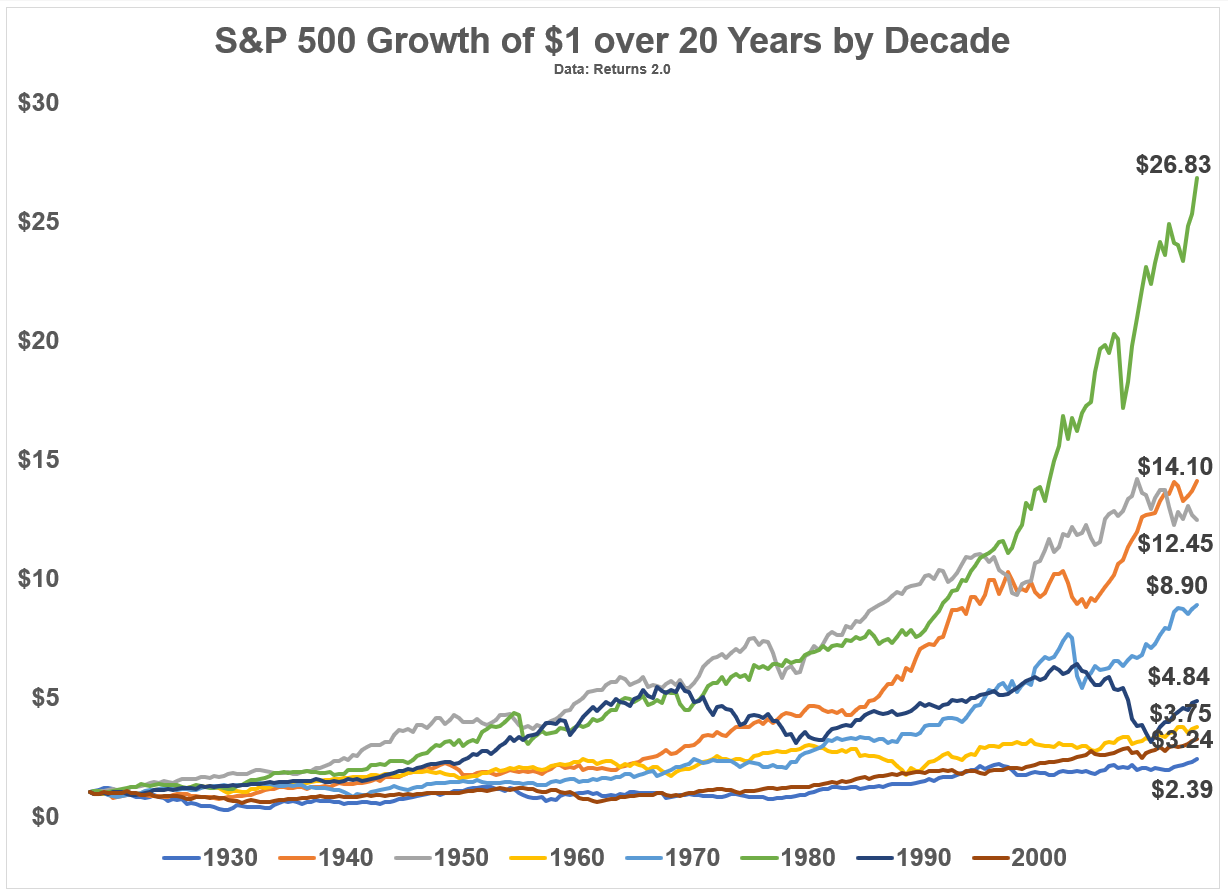

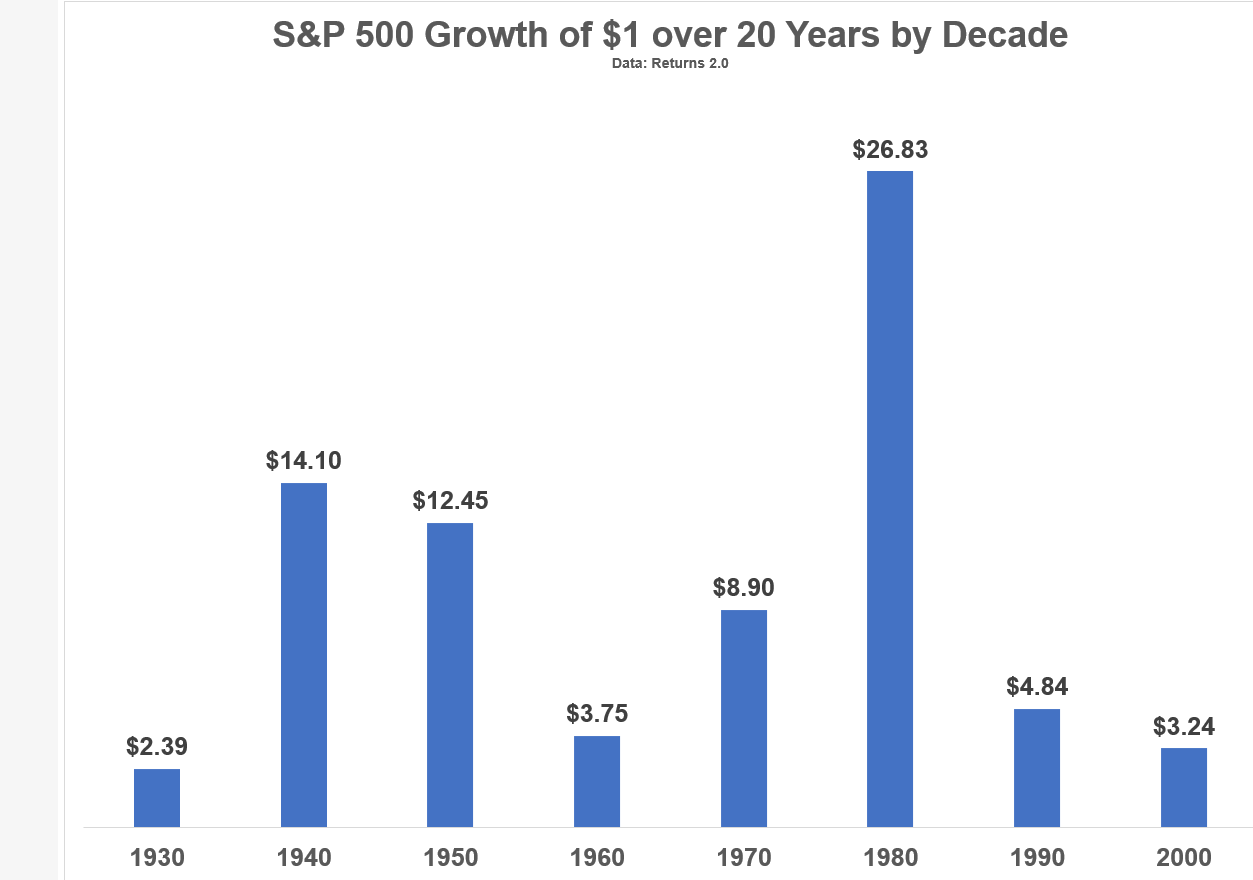

I calculated the growth of $1 invested in the S&P 500 over a 20 year period at the start of each decade going back to the 1930s:

There’s a wide range of results, to say the least.

Here’s another way of looking at these numbers: FIX CHART

Start investing in 1980 and it looks easy. Start in the 1930s and you probably want nothing to do with stocks.1

It’s also important to note “bad” markets with poor returns aren’t necessarily a poor outcome for everyone.

If you’re a net saver, you should want crappy returns, especially early in your career.

Risk means different things to different investors depending on their stage in life.

Unfortunately, there are many variables outside of your control when it comes to investing.

You can’t control the timing or magnitude of returns the markets offer. You also don’t control interest rates or inflation or economic growth or tax rates or the labor market or the actions of the Fed and politicians.

Life would be easier if you did but no one said life is easy.

The best you can do is focus on what you can control — your behavior, your savings rate, your asset allocation, your costs, your time horizon — and play the hand you’re dealt.

Further Reading:

The Mental Account of Asset Allocation

1I could have adjusted these results for inflation because that’s what everyone asks me for these days but you get the idea.