A reader asks:

I’m finding it incredibly hard to invest my excess cash, even in my kids’ college funds, with the S&P 500 closing in on new highs. Objectively, I know I’m supposed to just grit my teeth and invest, not try to predict the market, take comfort in knowing that time-in-the-market is biggest factor in my long-term investment success…but IT IS SO DAMN HARD for me to do it psychologically in these seemingly overbought conditions. I’m not an idiot: I do automatically max out my 401k. I’ve swallowed hard and contributed a fair amount to 529s, and even a bit to my brokerage account. But I have money building up on the sidelines that I know I should do something with, and every day the market hits a new high, I feel more paralyzed. Would love to see you tackle this “problem” because I know I’m not the only one suffering from this strange — and yes, enviably — malady.

For some investors this will always be a problem.

Market timing is hard. And once you do it, market timing can lead to a cash addiction.

When markets are falling you assume they will fall even further. Cash becomes a safety blanket.

When markets are rising you assume they are too expensive and will correct at some point. Again, cash becomes a safety blanket.

I heard from an investor a number of years ago who went to cash in 1999. That was pretty good timing, considering it was the height of the tech bubble, which was the most expensive the U.S. stock market has ever been.

Unfortunately, he was still sitting in cash 15 years later.

He told me it was some combination of fear, arrogance and macro doom and gloom that kept him in the investment fetal position for a decade-and-a-half.

Market timing is hard not just because you need to be right twice for it to work — when you get out and when you get back in. It also requires the courage to get back in when you don’t want to.

There are a few ways around these fears.

I’ll start with the spreadsheet strategies and then move on to the behavioral approaches.

Diversification and asset allocation are risk mitigation strategies. You wouldn’t have to spread your bets if the future was known with certainty.

The whole idea behind setting an asset allocation in the first place is that it helps you balance your various risks and time horizons as an investor. You don’t have one asset allocation for bull markets and another for bear market or one for inflationary environments and another for deflation and so on.

You should have a mix of stocks, bonds, cash and other assets that is durable enough for you to hold during any market environment. That should be true of both current assets in your portfolio and any future contributions.

And if you’re that worried about valuations for large cap U.S. stocks you should look into diversifying into other asset classes — bonds (which finally have some yield), international stocks (much cheaper), value stocks (same), small cap stocks (also inexpensive), high quality stocks, dividend stocks, REITs, etc.

There are so many different strategies available today for you to diversify into.

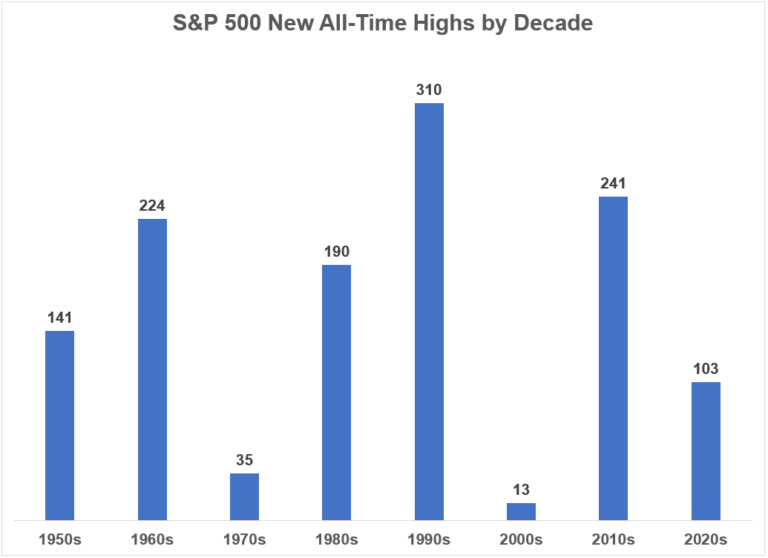

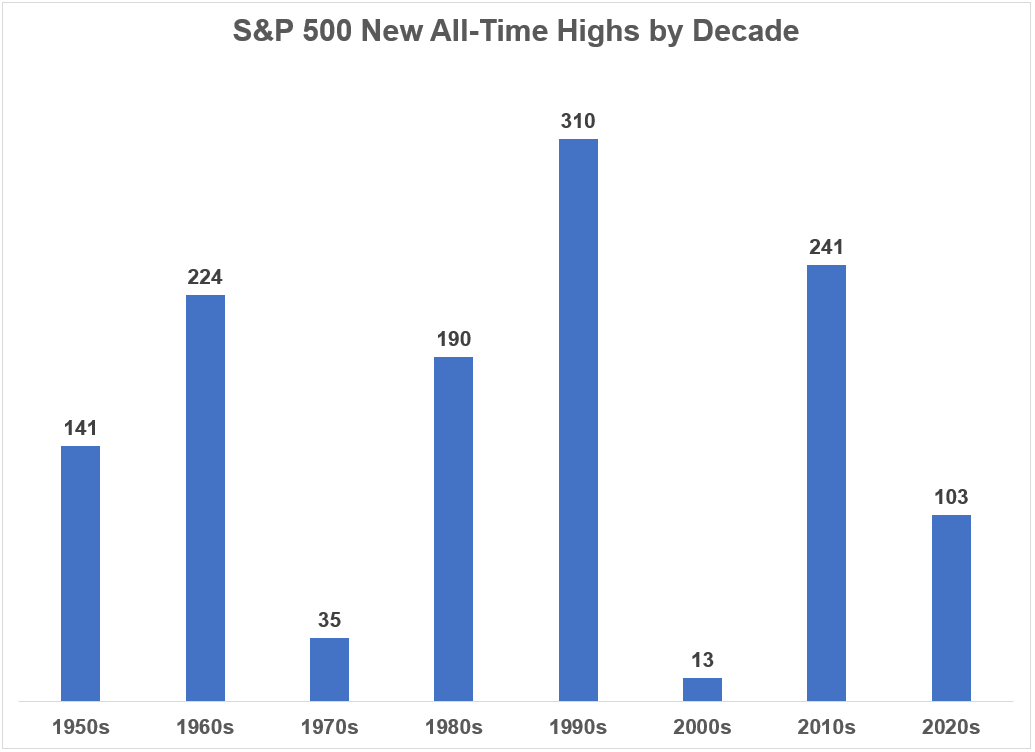

It’s also worth pointing out new highs in the stock market are nothing to be afraid of. They happen a lot:

A handful of these new highs will occur at a peak right before a bear market. But most of them simply lead to more new highs down the road.

The other big piece here is defining your goals. Why are you investing this cash in the first place?

Retirement? A trip to Hawaii? Renovations? Kid’s wedding? Beach house? Healthcare needs? General rainy day savings?

The sole goal of investing is not finding the highest returns you can or creating the most optimized Sharpe ratio portfolio or outperforming some benchmark. You invest money now in the hopes that it grows to a larger amount for future use.

You just have to define those future uses and when they will occur.

Your money is all in one big bucket but you can separate your portfolio into different buckets if that helps. One bucket can be for growth. Another can be for income or volatility reduction. Another bucket could be for capital preservation or safety.

That safety bucket can and probably should include cash (short-term bonds, CDs, money market funds, online savings accounts, etc.). But I like the idea of putting a limit on the cash piece of your portfolio.

That could be a percentage of the overall allocation or an absolute level.

My cash bucket has a ceiling on it. Once a pre-defined level is breached, I move anything over and above that amount into my investment accounts. It doesn’t have to be set in stone but you should set that number in advance so you’re not guessing all the time or slowly becoming addicted to a growing cash position.

The point is every piece of your portfolio should have a job. And those jobs should be defined in advance along with the resources necessary to complete them.

Of course, the plan is the easy part. Anyone can do that.

The hard part is implementing your plan.

Your only choice here is automation.

Automate your contributions. Automate your asset allocation. Automate your rebalancing schedule.

And then stop looking at your portfolio so much.

The best way to avoid mistakes in your portfolio is to make a handful of good decisions ahead of time and get out of your own way.

We spoke about this question on this week’s Ask the Compound:

Barry Ritholtz joined me again this week to cover questions about the state of the economy, bond yields, investing an inheritance and collectibles.

Further Reading:

The Psychology of Sitting in Cash