A reader asks:

I like the idea of a modified version of the FIRE (financially independent, retire early) movement known as “coast FIRE” where you hit a principal savings goal and then never have to save a dollar again for retirement. For example, currently have no debt and $50k earmarked for retirement. I’m 30 and it’s highly unlikely that I would never contribute to this portfolio again. If I added $200/month between my wife and I for the next 35 years (lord willing) at a 7% return I get a balance of $935k. Why is it that many think you need $1-3 million in retirement when to me assuming a 7% return is already more on the conservative side and obviously Social Security will also most likely still be around. What am I missing?

This coast FIRE strategy makes sense in theory.

You frontload your retirement contributions when young and allow compounding to do the heavy lifting for you on the backend. That would mean less money you have to put away for the future.

I like some of the ideas behind the financially independent, retire early lifestyle. The high savings rate. The long-term planning ahead for the future. The discipline involved in the process.

There are other parts I don’t care for. Delayed gratification is part of any savings strategy but I don’t love the idea of young people foregoing their youth just so they can stop working. You should enjoy yourself when you’re young. There’s nothing wrong with spending some of your hard-earned money and having some balance in life.

To each their own. There are no perfect retirement strategies.

As a 30-year-old with no debt and $50,000 saved, you’re in a pretty decent place financially.

It’s possible this strategy will work but there are some questions you should ask yourself before implementation:

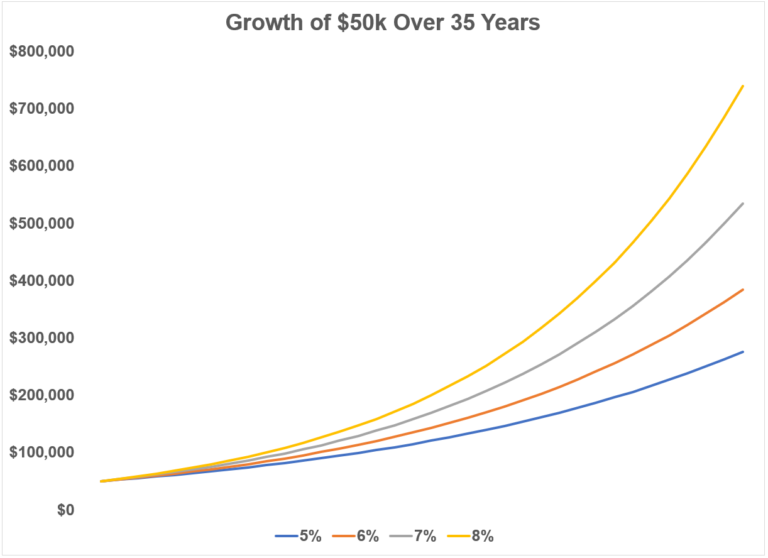

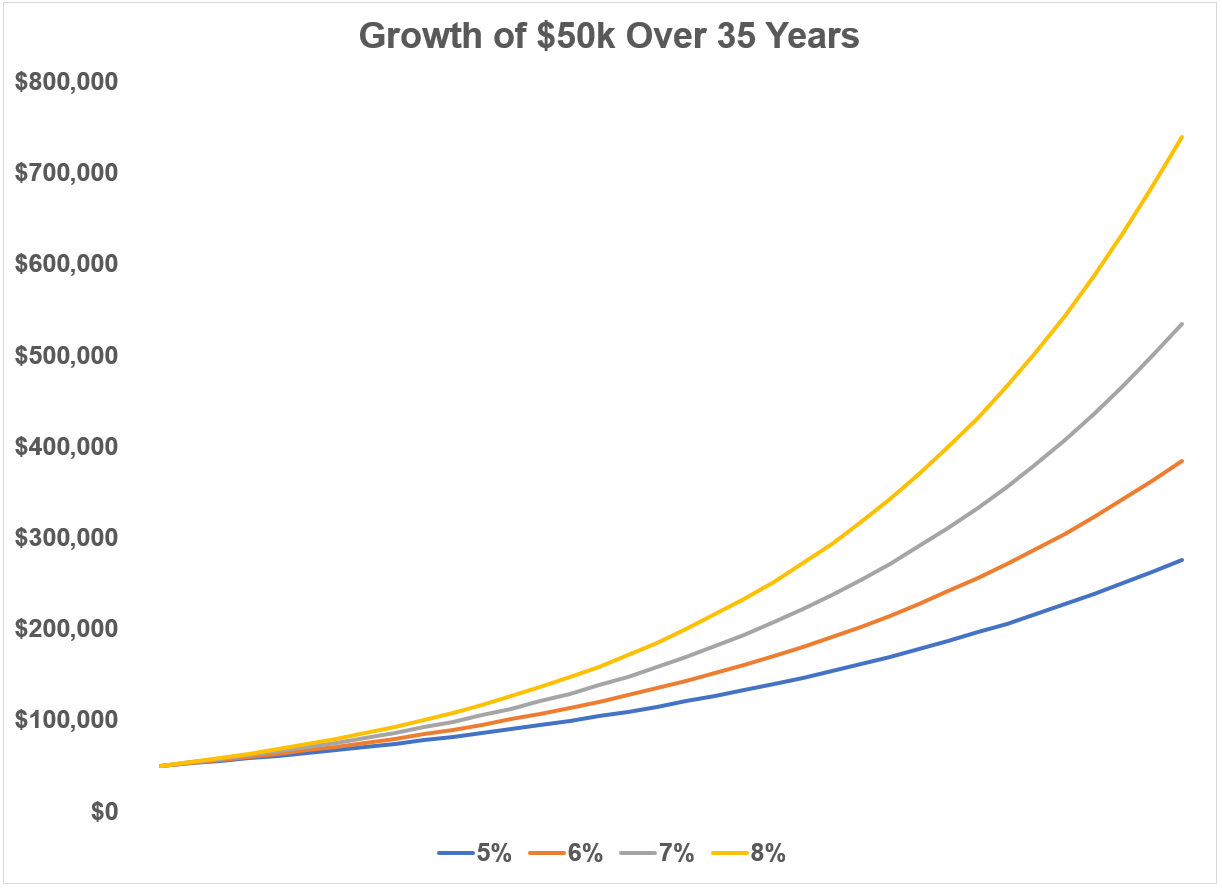

What if returns are lower? If you grow $50k at a 7% annual rate that would grow to more than $530k in 35 years.

If returns were 8% annually, that turns $50k into nearly $740k. Add that $200/month and now we’re somewhere in the $900k to $1.1 million range at 7% and 8% returns, respectively.

But what if returns are only 6% from here? That turns $50k into $384k. Returns of 5% would give you a balance of just $276k after three-and-a-half decades.

Even with your $200/month in savings that bumps you up to $493k and $652k.

Maybe with Social Security that’s still enough for you but lower returns could severely crimp your lifestyle if you’re banking on compounding to lead the way.

What if your lifestyle changes? The road that runs by my office was in serious need of repair a couple of years ago. It was two lanes along with a center turn lane but it was littered with pot holes.

For some reason when they tore it up the new design did away with the center turn lane. Instead, they added a median with some grass and trees to make it look nice along with some turn lanes along the way.

There was a problem with this design.

The road leads to all sorts of retailers, stores and restaurants. There are semi-trucks constantly driving this route to drop off inventory to these businesses.

The problem is they made the lanes too narrow for these mammoth trucks to turn in and out of the entrances. To get a wide enough turn the truck drivers were forced to drive on the median or lawn. The new design was ripped to shreds in a matter of days.

Months later they were forced to come back to knock back the medians at multiple spots and make the entrances wider to accommodate the semis.1

The designers made plans that looked good on paper but left no margin of safety.

You can create a retirement plan that looks good on a spreadsheet but it’s a good idea to give yourself some wiggle room in case things don’t go according to plan.

Your life in your 40s, 50s and 60s will look much different than life in your 30s. You might take on some debt. You might have some kids. You might go back to school. Maybe you’ll decide the FIRE movement isn’t for you.

Everyone is forced to forecast their future self when planning for retirement but it’s silly to assume your standard of living at 30 will remain your standard of living at 65.

Allowing for a margin of safety with your finances gives you some breathing room when life or preferences change.

What about inflation? The historical rate of inflation in modern economic times in the United States is roughly 3%. Over 35 years, 3% inflation turns $1 into 37 cents.

A 2% inflation rate cuts your dollar in half over 35 years. Bump it up to 4% and $1 becomes 26 cents.

The numbers your coast FIRE plan spits out may seem completely doable today based on your current level of spending.

That money won’t take you as far as you think in the future.

There are no guarantees when it comes to retirement planning that extends many decades into the future. There are simply too many variables.

This is how you can give yourself a margin of safety just in case things don’t go as planned (and they never do):

Move from a dollar amount to a % of your income for savings. Aim for a savings rate of your income as opposed to a dollar amount you save each month or year. That way your savings (and spending) level will grow with your income.

Increase your savings rate a little bit each year. Let’s say you make $60k a year and save your $200/month. That’s a 4% savings rate. If you saved the $2,400/year that would add up to $84k in savings over 35 years (before any investment growth).

Now let’s assume you get a 3% raise each year. Instead of saving a static $2,400 you shift to saving 4% of income each year. Then let’s increase that 4% saving rate by 3% each year.2 That would more than triple the amount you save over 35 years to more than $272k.

Then you make course corrections to your plan as time goes by and life inevitably gets in the way.

You can still allow your initial investment to coast into retirement but making some tweaks to your plan gives you some more flexibility and a bigger margin of safety.

We discussed this question on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Nick Sapienza joined me on the show this week to go over questions about inflation, concentrated stock positions, investing in strategies with amplified volatility, and which retirement accounts are the most important savings vehicles.

Further Reading:

The Evolution of Retirement

1There was even a story in the local paper where the architects of the plan defended their design. They claimed it was good. It was not. The trucks are still forced to drive on the grass at certain locations along the narrow roads. And they didn’t put in enough places to make turns, which essentially makes it a one-way street at certain points along the way. No, I’m not bitter, why do you ask?

2I’m not even talking about going from 4% to 7%. A 3% growth rate would take 4% to 4.1% to 4.2% to 4.4% to 4.5%, etc.