A reader asks:

I get all the stuff Ben has been saying about inflation — wages have kept pace, economic growth has been higher than the 2010s, wages have risen the most for lower income people, etc. I get all that. My husband and I own a house and own stocks so we’ve benefitted in recent years. Having said all of that, I STILL CAN’T GET OVER HOW HIGH PRICES ARE!!!

The grocery store, home/auto insurance, restaurants, babysitters for the kids…everything is more expensive.

So how do I get over the sticker shock? Will it just fade eventually as we get used to higher prices?

The psychological component of inflation is obviously a real phenomenon.

One of the reasons for this is because inflation is personal.

Much like any given year in the stock market is rarely average, no household experiences the average inflation rate as reported by the government. Not only is inflation basically impossible to calculate precisely, but everyone’s circumstances are different.

If you own a home, locked in a 3% mortgage, don’t carry a lot of debt and own financial assets, you should be fine, relatively speaking.

If you’re a renter, looking to buy a home, need to buy a new car or need to borrow money, this environment has been a killer.

This is why so many people don’t believe the inflation numbers.

The average inflation rate includes a wide range of results across different households. Many people have been harmed by inflation through no fault of their own while others have made it out more or less unscathed through sheer luck.

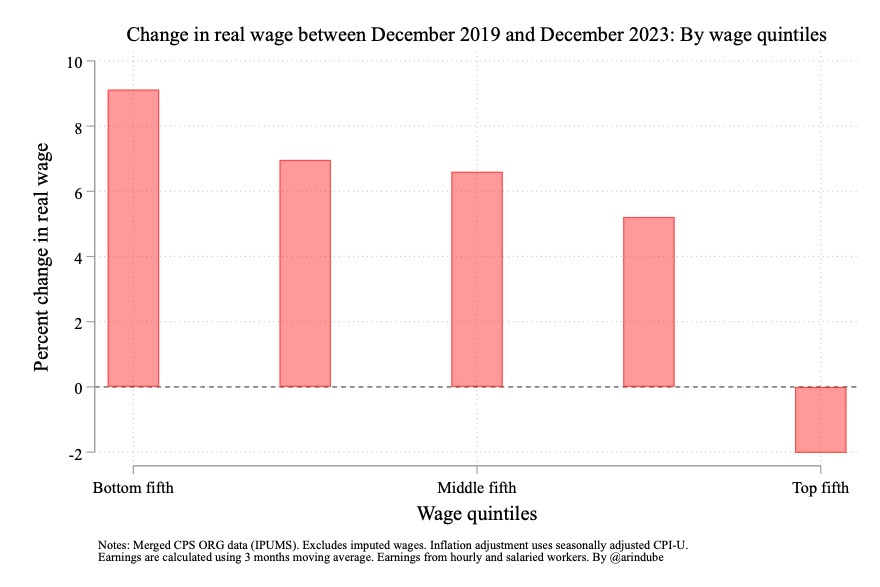

The same is true when it comes to wages. Arin Dube calculated the real wage change by income quintiles from the end of 2019 through the end of 2023:

It’s true that lower wage workers have seen the biggest uptick in wage growth, even after accounting for inflation.

But this is also an average number. Some have fared better, others worse. Some of these people own a home, some don’t. Some own stocks, most don’t.

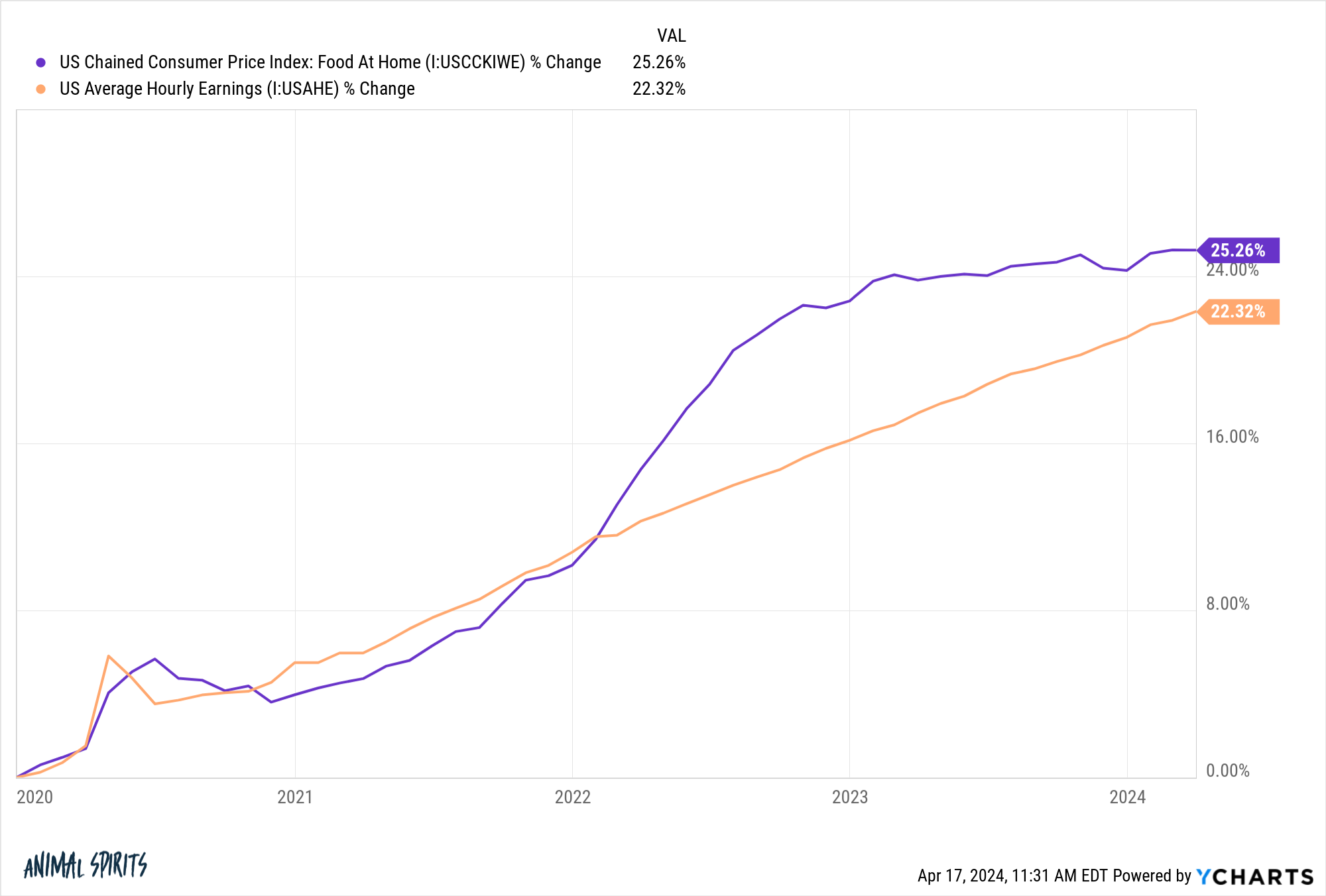

If groceries are one of your biggest expenses, you’re in a world of pain:

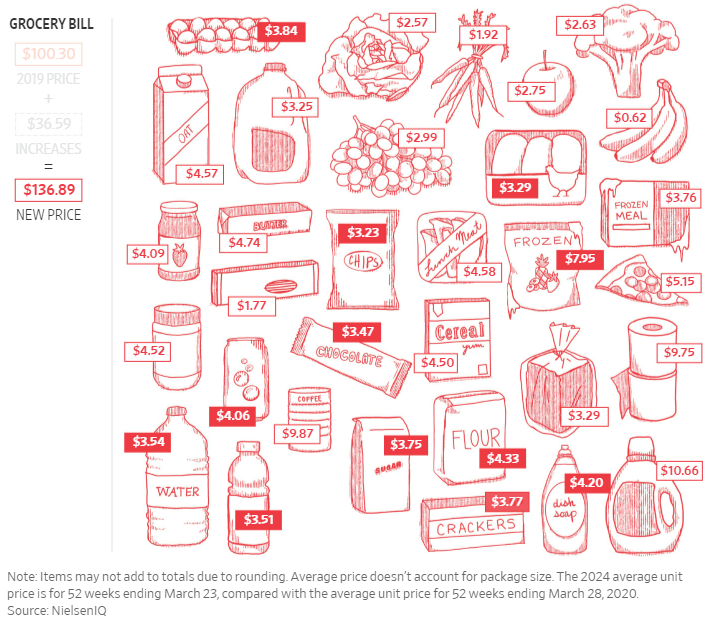

And this inflation is also not necessarily correct depending on what you shop for. The Wall Street Journal looked at changes in the average price for various grocery store items since 2019:

They found this list of staples you buy at the grocery store has risen 36% since 2019. To be fair, you have to adjust these prices for wages, too, but these are the prices people experience on a regular basis.

There are obviously people who are struggling with higher prices because of their circumstances, but the person asking this question admits they are doing just fine financially speaking. So why is inflation so psychologically impactful even if you’re not in the struggling class?

For one, wages feel like they’re deserved while inflation feels unfair.

The loss of purchasing power stings far worse than the gains you experience over time in wages. Inflation is loss aversion on steroids.

The fact that inflation occurred in such a compressed period of time plays a role here as well.

For example, CPI was up roughly 20% for the entirety of the 2010s decade. Prices were also up 20% from 2020-2023. It’s the same magnitude of price changes but the fact that they happened so quickly this decade introduces recency bias.

In the 2010s you had the opportunity to become accustomed to the prices changes because they happened slowly over time. In the 2020s, it was an all-out blitz of price increases.

And while grocery store prices seem out of control of late, the story looks much different over the course of this century:

Wages have far outpaced grocery store prices and grocery store prices have actually grown less than the overall rate of inflation since 2000. Those gains occurred over time while the losses happened immediately. Inflation feels worse when it happens in a hurry.

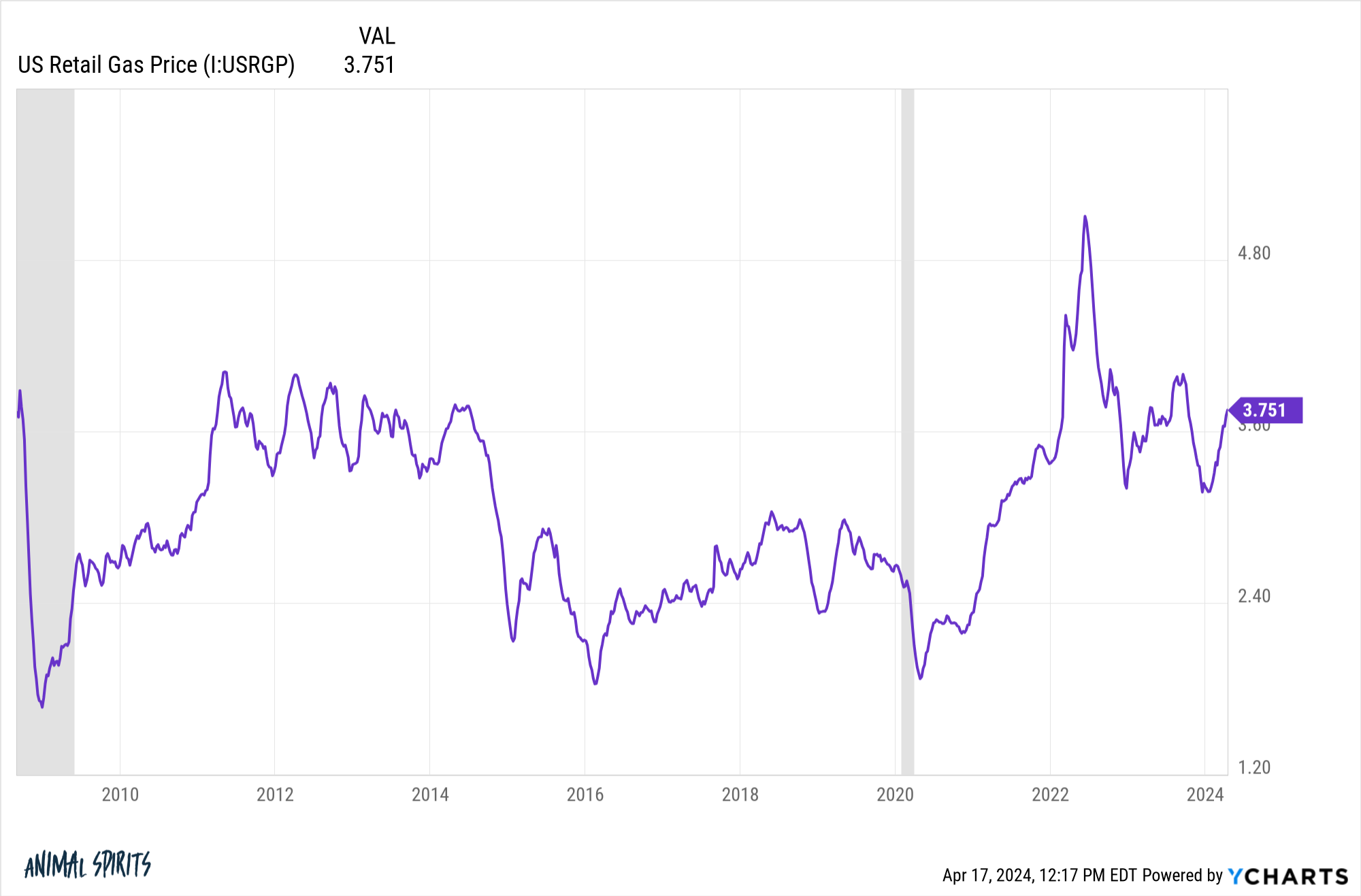

Or look at gas prices. They’re at the same level now as they were in September 2008:

If you adjust gas prices for inflation, they’re down 30% or so since 2008. But we don’t feel those inflation-adjusted gains. We only feel the losses when gas prices rise from lower levels.

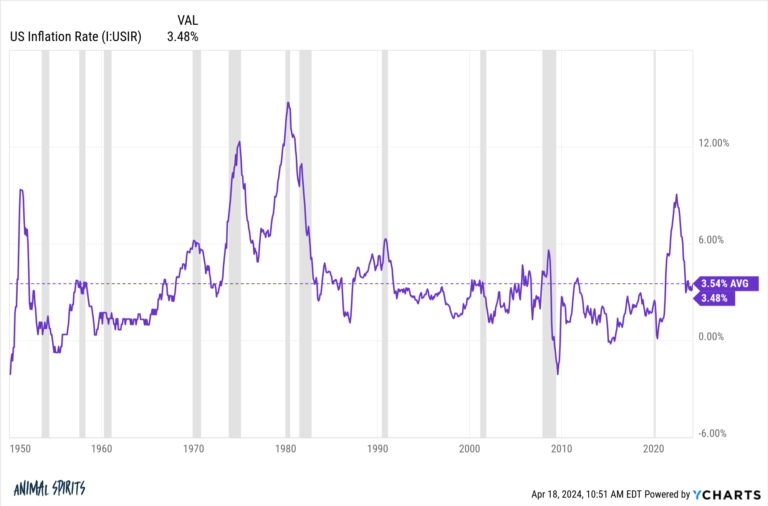

The other important point to remember is that price levels rarely go down as a whole. Here’s the annual inflation rate going back to 1950:

Prices have fallen just 3.7% of the time. That means 96.3% of the time, prices have been rising. The worst bout of deflation was during the 2008 financial crisis, at -2.1%, and it didn’t last.

Eventually people will get used to higher prices.

The funny thing is today’s prices will seem low compared to future price levels.

We covered this question on the latest episode of Ask the Compound:

Jill Schlesinger joined me live in studio to go over questions about pensions with retirement planning, using a HELOC for home equity, dealing with stocks that have big taxable gains, buying a new car to minimize fuel costs and how to insulate your career from the robots and AI.

Further Reading:

The Pros & Cons of More Volatile Inflation