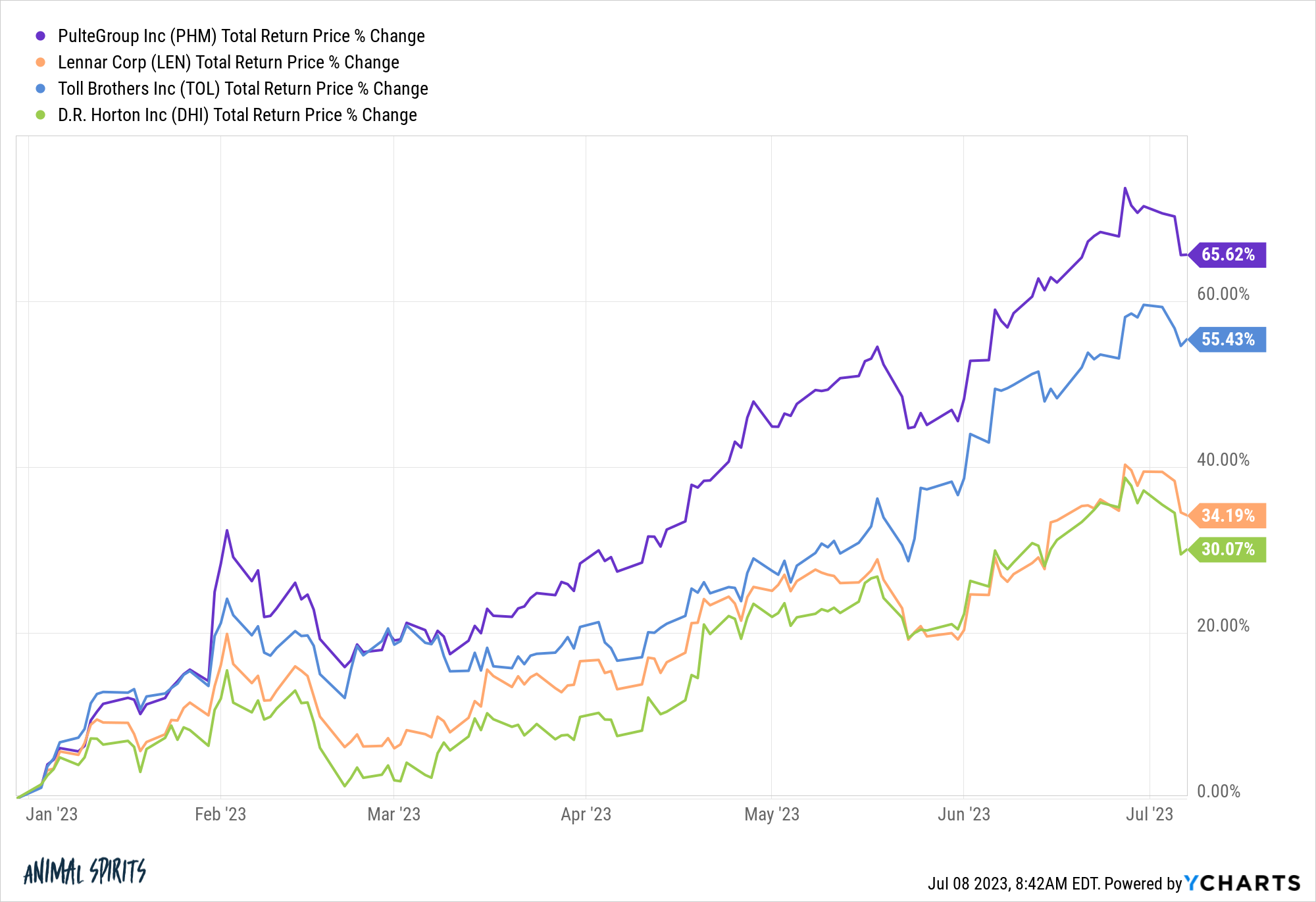

For the longest time pundits predicted interest rates would go higher yet they did nothing but go lower year after year.

Then when rates hit 0% it seemed like everyone assumed we would experience lower rates forever…just in time for rates to rise higher than anyone thought was possible in such a short period of time.

So it goes when it comes to the markets.

When rates first began going up it seemed like it was only a matter of time before the Fed would break something and ZIRP would be back in our lives in no time.

But a funny thing happened — rates went up an extraordinary amount and nothing really broke. Not yet anyway.

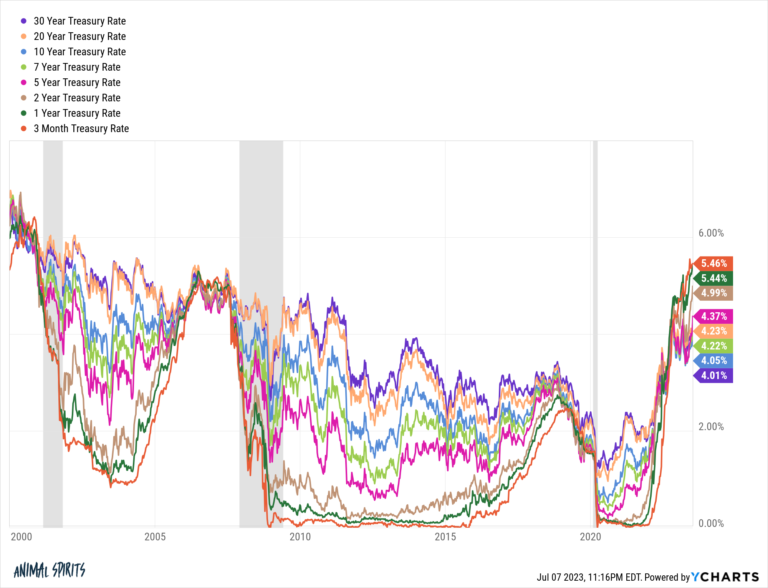

Here’s a look at current U.S. government bond yields:

There are all sorts of crazy things going on here when you consider how inverted the yield curve is, the speed of the rise in rates and the absolute level of yields that we haven’t seen — at least on the short end of the curve — in decades.

So when is it all going to matter?

There are three areas of the markets and economy that I have this very same question for:

When do rates begin to matter to the stock market? There was a story in the Wall Street Journal this week about the substantial increase in equity allocations by older investors:

Nearly half of Vanguard 401(k) investors actively managing their money and over age 55 held more than 70% of their portfolios in stocks. In 2011, 38% did so. At Fidelity Investments, nearly four in 10 investors ages 65 to 69 hold about two-thirds or more of their portfolios in stocks.

And it isn’t just baby boomers. In taxable brokerage accounts at Vanguard, one-fifth of investors 85 or older have nearly all their money in stocks, up from 16% in 2012. The same is true of almost a quarter of those ages 75 to 84.

There are a few different reasons for this drift higher in stock ownership.

Older investors have been through more bear markets and have seen the benefits of investing in stocks over the long run.

Some people likely needed to take more risk because they didn’t save enough.

But we also went through a lengthy period of low interest rates in the 2010s where people were forced out on the risk curve.

Today it’s the opposite.

You can earn nearly 5.5% in 3-month T-bills right now. That’s the highest level since early-2001. Short-term yields haven’t been above 5% since 2007.

Conservative investors of the world should rejoice, especially if the Fed is able to keep rates higher for longer.

But when will we start to see investors become more conservative with their allocations now that risk-free rates are so high?

And how will this impact the stock market?

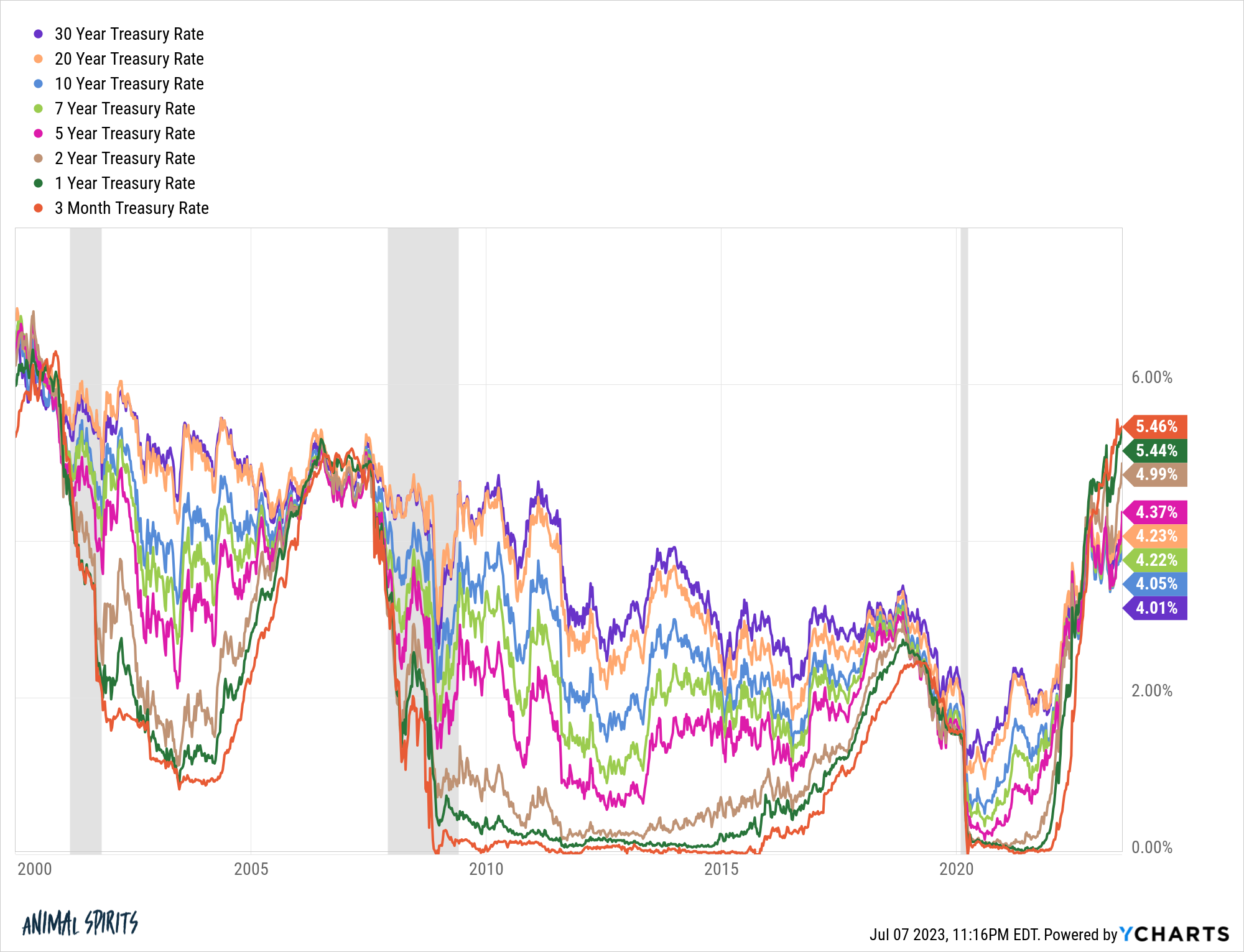

When do rates begin to matter to the housing market? Mortgage rates have shot back over 7% in the past couple of weeks:

But these higher rates haven’t deterred certain parts of the housing market.

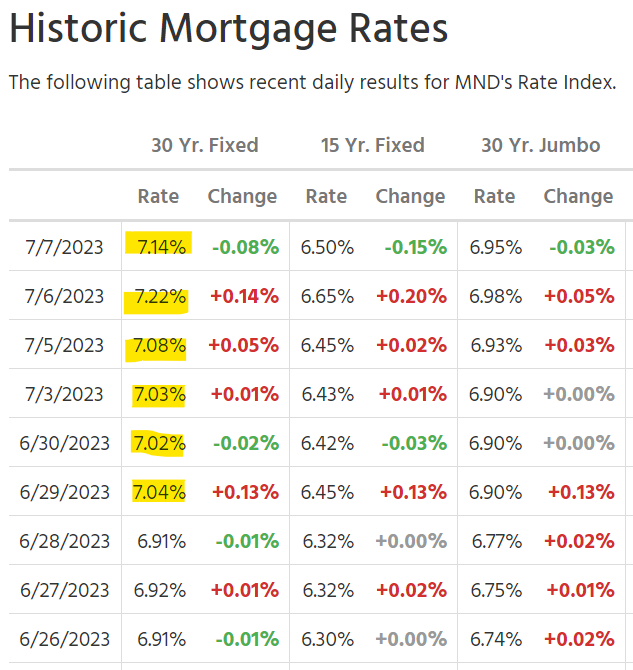

Homebuilder stocks are rocketing higher this year:

Pulte, Lennar, Toll Brothers and D.R. Horton have all hit new all-time highs this year despite mortgage rates going back above 7%.

There are so few existing homes on the market that homebuilders have become the only game in town for many buyers.

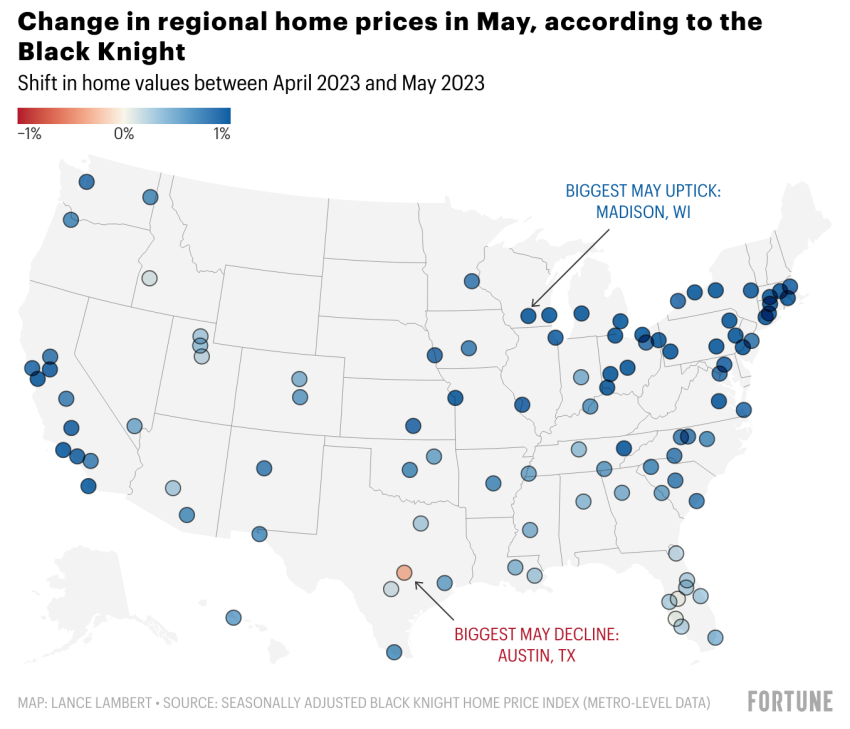

Housing prices are rising again too. Fortune’s Lance Lambert looked at the changes in regional home prices in May:

Ninety-nine of the nation’s largest housing markets saw price increases in May. The lone decliner was Austin, TX.

Ever since the pandemic we’ve lived through one of the strangest housing market cycles in history.

At some point, you would assume mortgage rates going from 3% to 7% would have an impact beyond a shrinking supply of homes for sale.

Housing prices and homebuilder stocks have been resilient (so far).

How long do mortgage rates have to stay elevated before the housing market finally gets dinged in a big way?

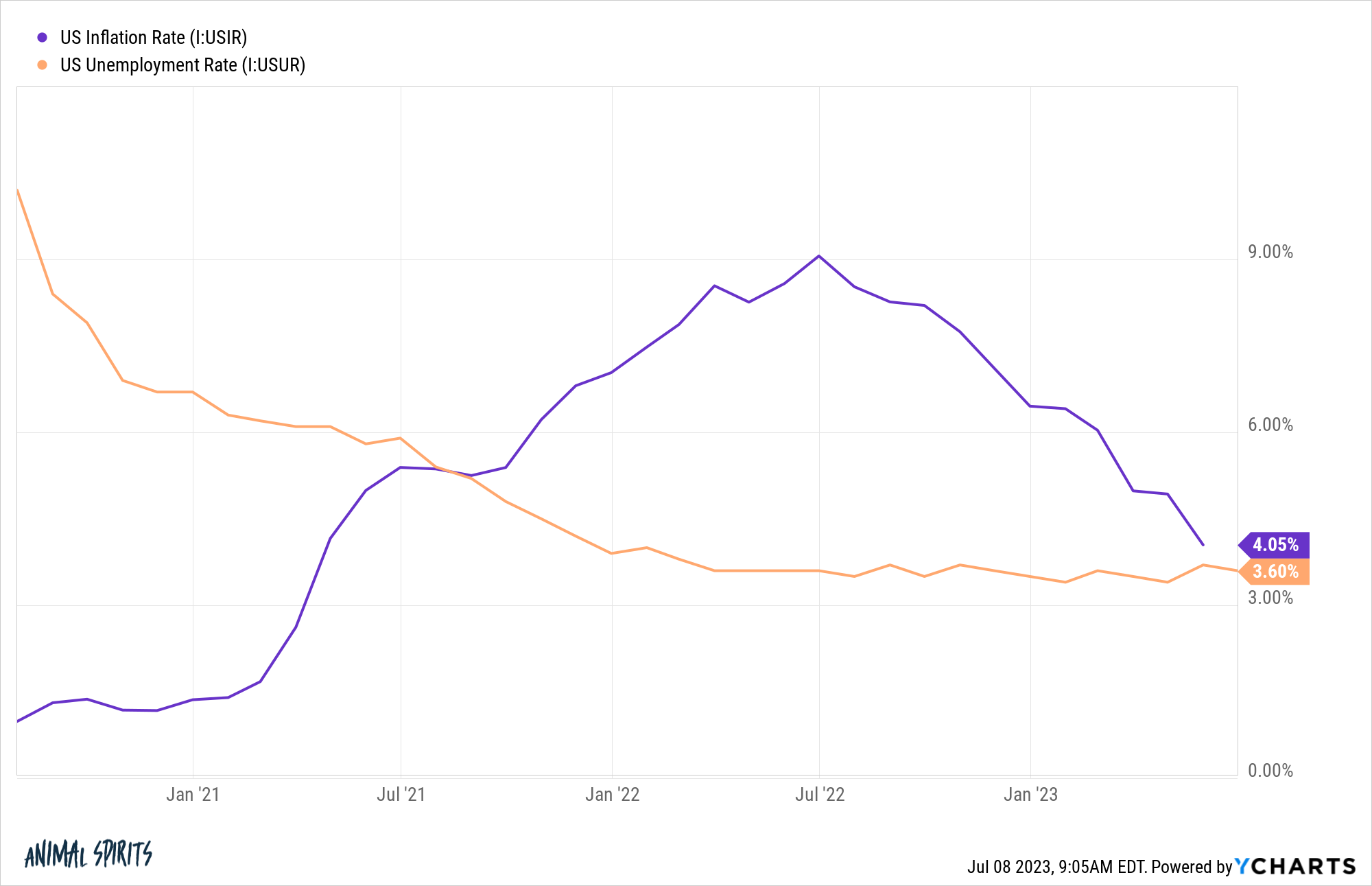

When do rates begin to matter to the labor market? Most economists and policymakers assumed we needed much higher unemployment to contain inflation.

Here’s what Larry Summers said needed to happen in a speech he delivered a little more than a year ago:

We need five years of unemployment above 5 percent to contain inflation–in other words, we need two years of 7.5 percent unemployment or five years of 6 percent unemployment or one year of 10 percent unemployment.

Since Summers made these remarks the U.S. economy has added more than 3.7 million jobs. The inflation rate has fallen while the unemployment rate hasn’t budged:

We’re living through one of the strongest labor markets in history and it doesn’t seem to care what economists or the Fed says or does.

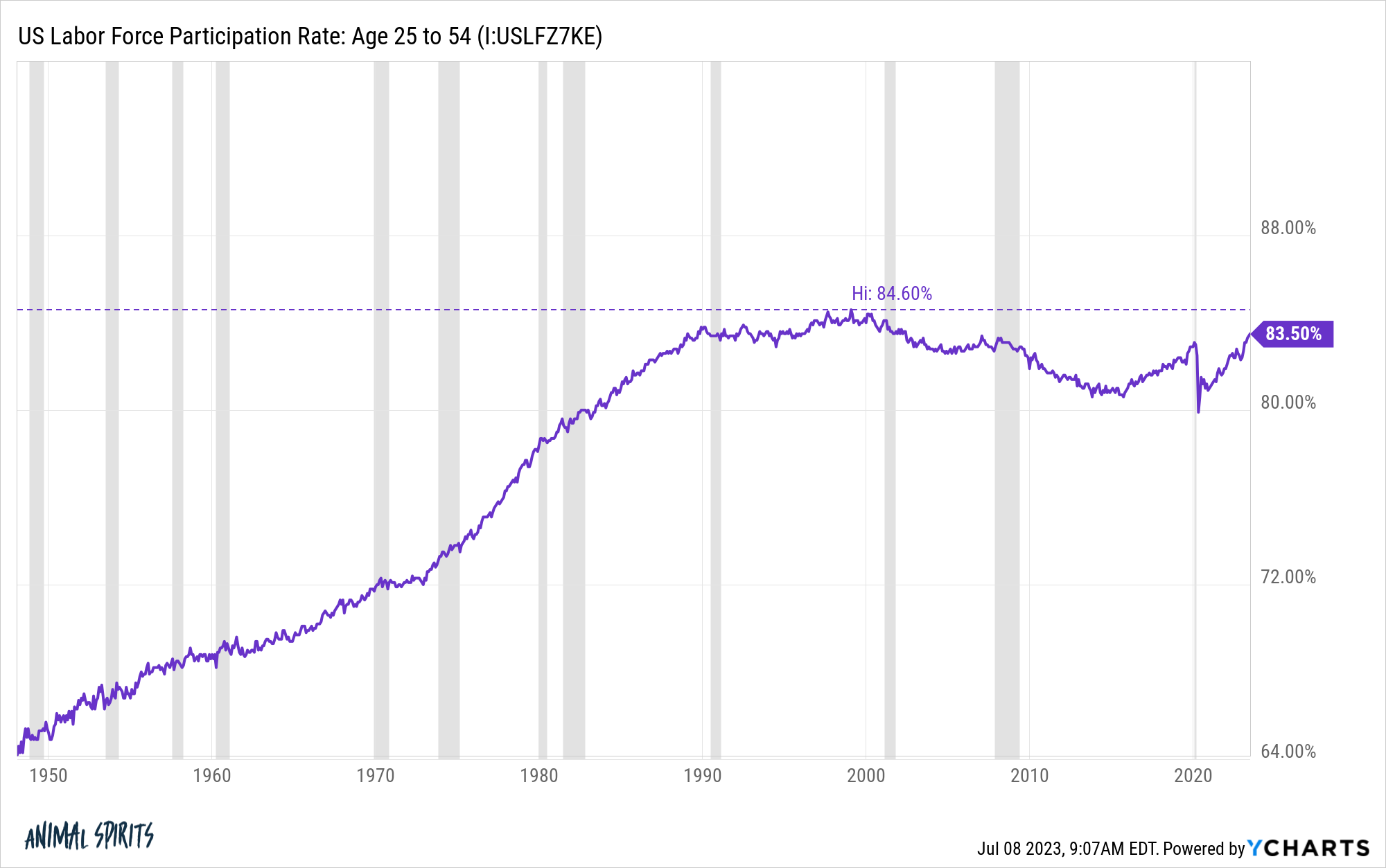

The prime age labor force participation ratio continues to rise, closing in on the all-time highs last seen in 2000:

Jerome Powell explicitly said he wanted people to lose their jobs to help with the inflation problem.

Well inflation has come down while the labor market charges on.

Can this last?

I honestly don’t know.

Many people think monetary policy works on a lag. If rates stay high, eventually consumers will blow through their excess pandemic savings, borrowing costs will become too prohibitive and the economy and stock market will falter.

You can’t rule out the potential for a lag if rates stay higher for longer. Eventually, you would assume 7% mortgage rates and 9% auto loan rates and 27% credit card rates would slow down the economy.

We’ve already put off a slowdown in economic activity for much longer than most experts assumed was possible.

I agree higher rates should have an impact at some point.

I just don’t know what the tipping point will be if people just keep spending money.

Further Reading:

What Happened to the Recession?