I read The World is Flat by Thomas Friedman when it came out in 2005.

This was one of the first books I read after graduating college that made me feel smarter. It felt like the world made more sense.

Globalization flattened the world. The Internet leveled the global economic playing field. Talent and ideas could come from anywhere in a world where borders didn’t matter as much anymore.

If you had asked me at the time for the investment implications of these ideas I probably would have thought you should buy the BRICS and sell America short (relatively speaking). That would have been the wrong move.

The U.S. stock market is up 11% per year in the 20 years since the book was published.1 The rest of the world’s stock markets are up 6.2% in that same time frame. The Chinese economy has outpaced our growth but the MSCI China Index is up 8% per year over the past two decades.

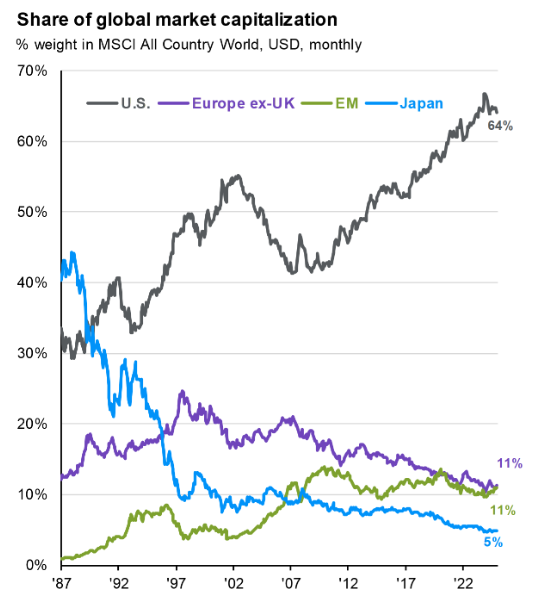

U.S. stocks represented around 45% of the world equity markets in 2005. Now it’s closer to 65%:

Coming out of the Great Financial Crisis, many allocators were still pounding the table to buy countries other than the United States. The idea was that economic growth would be higher in these other countries, and equity returns would surely follow.

Obviously, no one saw the tech boom coming.

Now it seems like the sentiment has completely shifted in the other direction. Because of the dominance of the U.S. tech sector and the sustained outperformance over the rest of the world since the 2008 crisis, many investors want nothing to do with foreign stock markets.

There are always people predicting an end to the Roman Empire so to speak when it comes to America’s place in the world order. What’s interesting is we already witnessed this to some degree with Europe over the past 100+ years.

Look at what Charles Emerson wrote about Europe in his book 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War:

A European could survey the world in 1913 as the Greek gods might have surveyed it from the snowy heights of Mount Olympus: themselves above, the teeming earth below.

To be a European, from this perspective, was to inhabit the highest stage of human development. Past civilisations might have built great cities, invented algebra or discovered gunpowder, but none could compare to the material and technological culture to which Europe had given rise, made manifest in the continent’s unprecedented wealth and power. Empire was this culture’s supreme product, both an expression of its irresistible superiority and an organisational principle for the world’s improvement. The flags of even some of Europe’s smaller nations – Denmark, Portugal, Belgium or the Netherlands – flew over corners of the wider world, whether a handful of islands in the Caribbean, a south-east Asian archipelago, or a million square miles in central Africa. Among Europe’s Great Powers only Austria-Hungary remained without a colonial empire. To be a European – to be a European man, in particular – was to see oneself at the centre of the universe, from which all distance was measured and against which all clocks were set.

If you erased the names and dates in those first few sentences it would basically be how you would describe the United States today.

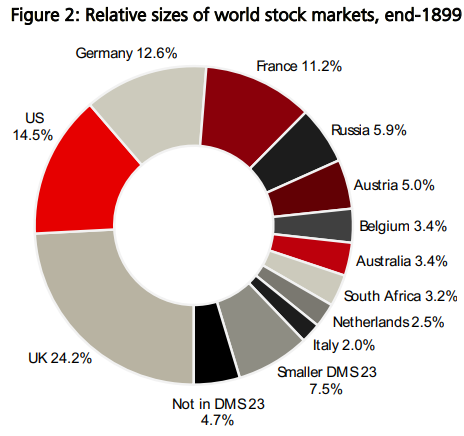

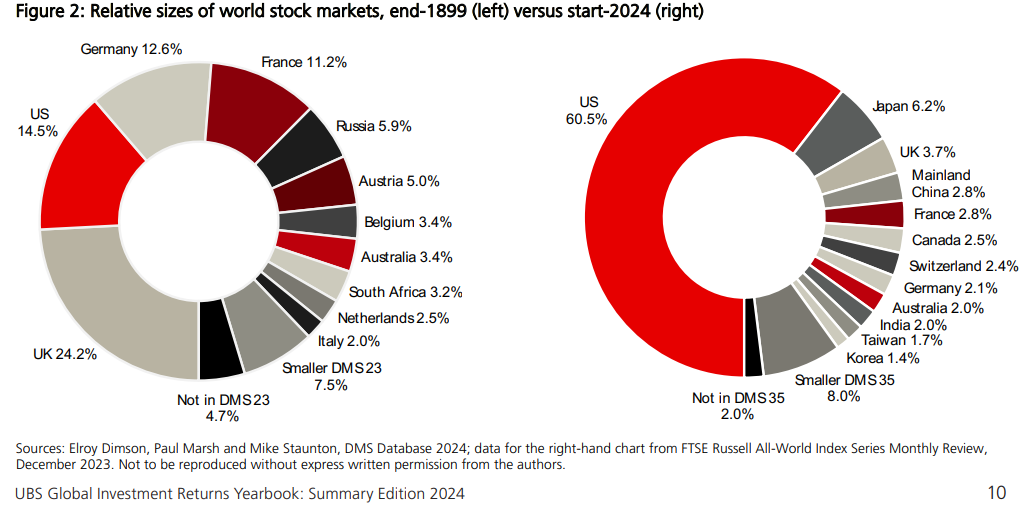

One of my favorite charts from the Global Investment Returns Yearbook shows the change in stock market weights from the start of the 20th century to today:

I don’t think people realize how well-positioned the United States was coming out of World War II or how devastated Europe was from the war. We’ve been an economic superpower ever since. Europe has stagnated.

European equity markets made up more than 60% of the global total heading into the 20th century. That’s where the United States is now.

Could the same thing happen to us? That wouldn’t be my baseline assumption but who knows.

I remain bullish on America over the long haul but I don’t know what’s going to happen going forward.

Maybe Friedman’s flat world thesis was just early? What if the dollar loses its place as global reserve currency? What if something totally unexpected changes the world order? What if we get complacent and blow our lead like Europe did? What if AI levels the playing field in ways we can’t possibly imagine?

Think about it from this perspective. The United States now makes up roughly:

- 4% of the world’s population

- 25% of the world’s GDP

- 65% of the world’s stock market cap

Will it always look like this?

Through the lens of recency bias I have no reason to believe the U.S. will relinquish our lead over the rest of the world when it comes to financial markets.

Through the lens of history I know the world is not a static place.

This is why international diversification makes sense to me.

America still has a lot of advantages over the rest of the world from an economic and markets perspective.

But I still think it’s prudent to own stocks all around the world because those advantages aren’t guaranteed to last in the future.

Further Reading:

Why I Remain Bullish on the United States of America

12006-2025 for these returns.