I recently wrote a short history of credit cards in America.

Here’s the short summary of consumer spending in the modern era:

Consumer credit took off for the first time in the Roaring 20s as Americans desired all of the new household innovations that came to market.

The Great Depression crushed the stock market, crushed the economy, crushed the consumer and turned a generation of households into penny pinchers who were too nervous to spend money.

After World War II that all changed as consumer credit exploded from the buildout of suburban America and the middle class.

Credit cards burst onto the scene in the 1960s which took spending up another level. Then the 1970s inflation hit and debt was actually an asset in some ways because purchasing power was being eroded so quickly.

By the 1980s and 1990s, consumerism and debt had taken over the average household’s mindset and bank account. We love to spend money in this country and we’re damn good at it too.

In many ways, the Great Financial Crisis was caused by the debt accumulated over the previous 30 years or so. That cataclysmic financial crisis was years in the making.

But after the 2008 crisis, households (on aggregate) learned their lesson. No more cash-out refinancing to take vacations or buy more houses. No more crazy NINJA loans.1 No more adjustable-rate mortgages. Households repaired their balance sheets.

Yes debt has continued to rise but that’s going to happen when the economy grows. The good news is that debt has risen at a much slower rate.

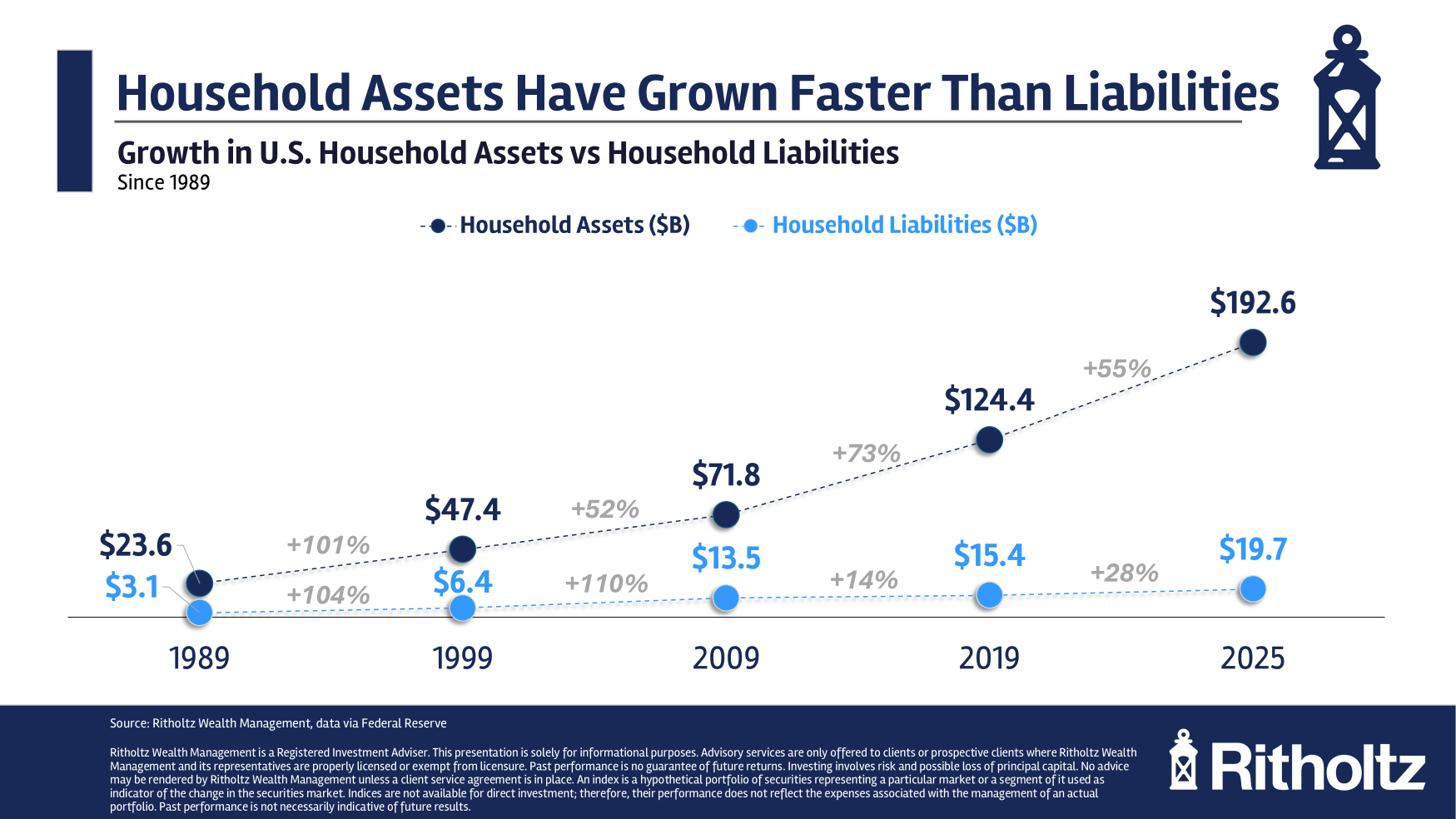

Take a look at the change in household assets and liabilities by decade going back to 1989:

From 1989-1999, the household assets and debt grew at a similar pace, both doubling in size. Then from 1999-2009, the debt grew much faster than the assets. Two recessions, a housing bubble and two stock market crashes had a lot to do with that but this was obviously not ideal.

Now look at what happened from 2009-2019 — assets grew way faster and the growth in liabilities slowed dramatically. The same thing has happened this decade as well. The growth in assets is outpacing the growth in debt.

That is why household net worth is at an all-time high.

Matthew Klein at The Overshoot tries to put the wealth gains this decade into context:

In other words, $66 trillion of net wealth was added in less than six years, equivalent to more than three times all of the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) in 2025.

Obviously, a booming housing and stock market have a lot to do with these gains.

The housing market is a perfect encapsulation of the differences between asset and liability growth this cycle and why this time is different.

In 2009, the total value of the housing market in America was roughly $19 trillion. Total mortgage debt outstanding was a little more than $10 trillion.

Today the housing market is worth $48 trillion while mortgage debt outstanding is $13.6 trillion. Mortgage debt makes up around 70% of total consumer debt.

To be fair, this was a once-in-a-lifetime housing price boom. Mortgage rates were at generationally low levels. This won’t last forever. But this is one of the reasons households are in a much better position from a balance sheet perspective than they were in previous cycles.

There is a case to be made that household balance sheets have never been in a better position than they are today.

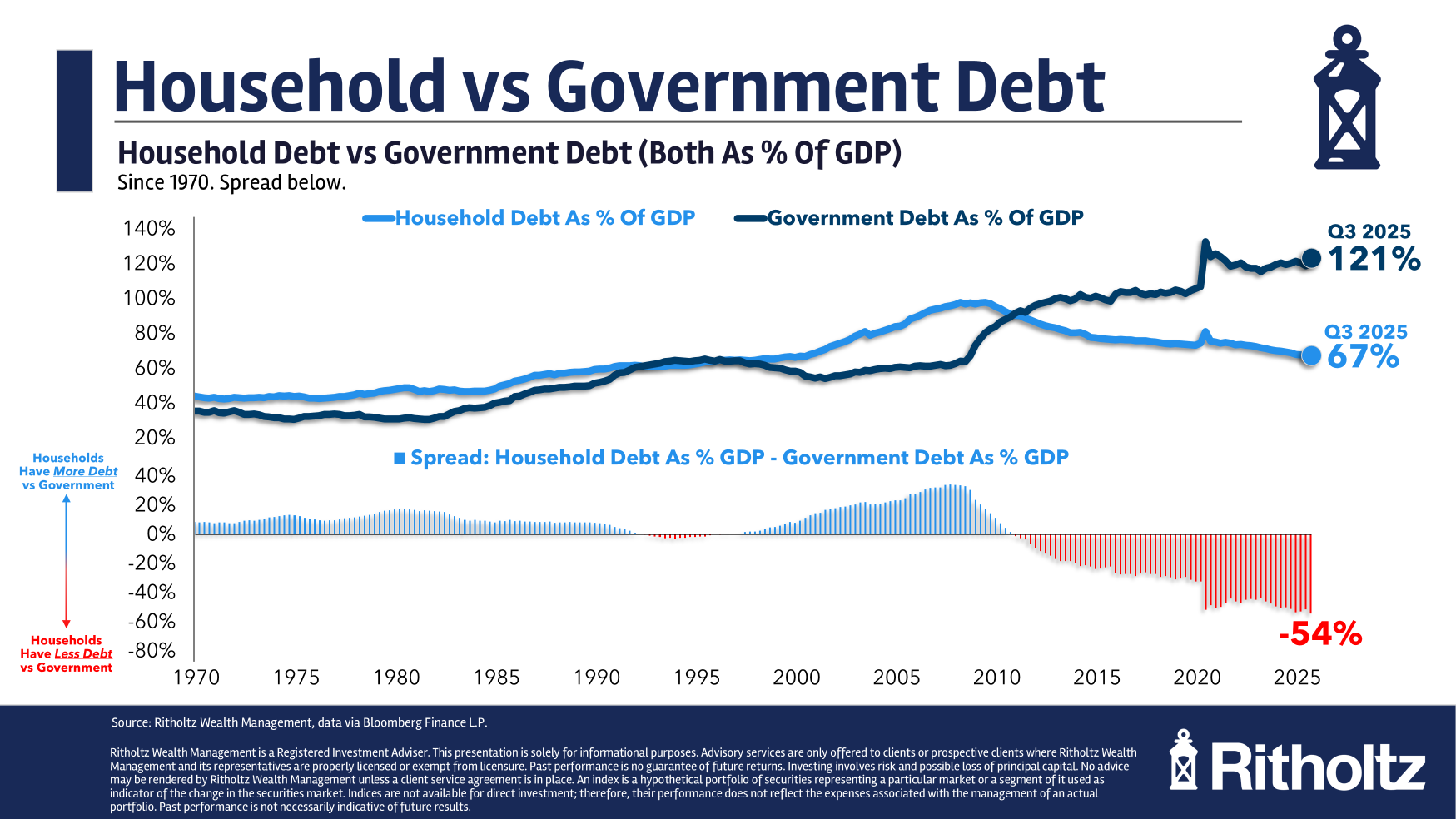

The counterargument is that household balance sheets are in such a good place because government debt is so out of control. Here’s a look at household and government debt-to-GDP going back to 1970:

As households repaired their balance sheets coming out of the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. government borrowed more money than ever. Government debt-to-GDP has skyrocketed while household debt-to-GDP has fallen considerably.

The government debt level is a topic for another time, but I would much rather have the institution that has the ability to print more of the global reserve currency and tax its citizens taking on more debt rather than households.

Household balance sheets won’t always look this clean. At some point this cycle will turn.

The economy will go into a recession. Asset prices will fall. Liabilities will rise as consumers borrow money to stay afloat.

But the good news is that households have never been better positioned to weather a storm. The capacity to borrow is now much higher because the growth in debt has slowed.

This is not like previous cycles.

This time really is different.

Further Reading:

Why Are Credit Card Rates So High?

1No income, no job, no asset loans were actually a thing in the lead up to the housing bubble.