Ray Dalio is back at it again, predicting yet another debt crisis in an interview with Bloomberg:

He gives us about three years until the U.S. has a heart attack from too much debt:

“I can’t tell you exactly when it’ll come, it’s like the heart attack,” he added. “You’re getting closer. My guess would be three years, give or take a year, something like that.”

Dalio is a billionaire who has made a lot of money in the markets over the years. Surely, we should listen to his warnings, right?

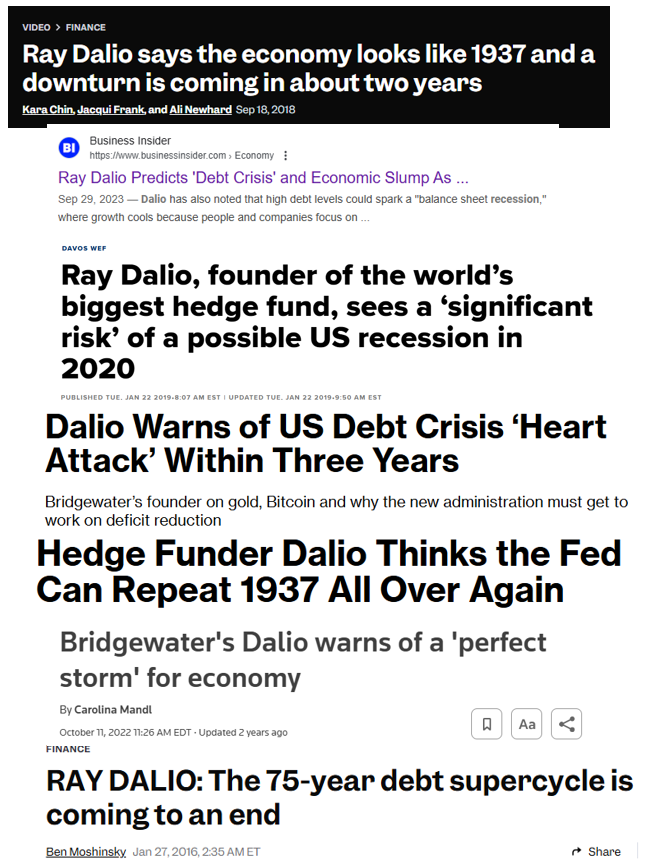

Maybe he’ll be right this time, but it’s worth noting that Dalio tries to predict a new financial crisis basically every couple of years.

Let’s take a look at his track record.

In the 2010s, Dalio was obsessed with the 1937 analogy.1 Here’s a piece from 2015:

Here’s another one from a few years later:

The 1937 panic was something of an echo recession that came on the heels of the Great Depression. Everyone thought the economy was out of the woods but that downturn led to a nasty 50% crash in the stock market. The unemployment rate went from 14% to 19% in a hurry.

That scenario would not have been very fun. Good thing we didn’t get the double-dip recession this time around.

Dalio likes to write about debt cycles so it’s no surprise he’s also tried to call the end of a debt supercycle a few times as well:

You have to admit that a supercycle sounds way cooler than just a regular old cycle.

Dalio was back at it in 2019 predicting a recession in 2020:

Technically he was right about this one. We went into a recession in 2020 due to Covid.

To be fair, there really is no way of telling if that prediction would have come true or not because the economic disruption from the pandemic was so severe. It’s possible we could have experienced a slowdown absent shutting off the economy in early-2020. Alas, there are no counterfactuals for these things.

Everyone predicted a recession in 2022. It was a question of when, not if. Inflation was high, the Fed was raising rates, and there was now a war in Ukraine. Dalio jumped on this train as well:

You know someone means business when they invoke the perfect storm analogy to forecast economic calamity. It’s never a good thing.

This was that perfect storm:

“The Fed and the government together gave enormous amounts of debt and credit and created a lurch forward. A giant lurch forward and created a bubble. Now they’re putting on the brakes. So now we’re going to create a giant lurch backward,” Dalio said at the Greenwich Economic Forum.

To fight inflation, Dalio said the Fed will continue raising rates. “And there’ll be real pain, of course,” he added.

Luckily we dodged that bullet too.

A year later Dalio was out with yet another debt crisis warning:

That drumbeat grows a little louder now with the heart attack analogy.

“Maybe the debt supercycle is on its last legs, and it will eventually turn into a problem of epic proportions.

Or maybe Ray Dalio is the boy who cried wolf.

Dalio is not one of those people who became obsessed with predicting financial catastrohphes coming out of the Great Financial Crisis. He’s been doing this for a long time. Dalio wrote about some of his biggest mistakes a decade ago:

The biggest of these mistakes occurred in 1981-’82, when I became convinced that the U.S. economy was about to fall into a depression. My research had led me to believe that, with the Federal Reserve’s tight money policy and lots of debt outstanding, there would be a global wave of debt defaults, and if the Fed tried to handle it by printing money, inflation would accelerate. I was so certain that a depression was coming that I proclaimed it in newspaper columns, on TV, even in testimony to Congress. When Mexico defaulted on its debt in August 1982, I was sure I was right. Boy, was I wrong. What I’d considered improbable was exactly what happened: Fed chairman Paul Volcker’s move to lower interest rates and make money and credit available helped jump-start a bull market in stocks and the U.S. economy’s greatest ever noninflationary growth period.

Dalio predicted a depression at the outset of what would become one of the biggest bull markets in history. There are plenty of other instances where Dalio’s predictions were on the wrong side of history.2

Perhaps the most impressive part of Dalio’s track record is the fact that these macro predictions haven’t really impacted Bridgewater’s performance numbers. It remains one of the biggest hedge funds in the world with an enviable long-term track record.

I think one of the biggest reasons for this is the fact that Bridgewater uses a rules-based framework that relies more on quantitative models rather than human forecasting ability.

That’s the way I think about macro forecasts as well. I have my opinions about what I think could happen. Some of them will be right. Most of them will be wrong.

My investment process does not change substantially based on those macro forecasts.

Your process shouldn’t change based on the forecast of a hedge fund manager either.

Further Reading:

Ray Dalio & The Power of Setting Defaults For Optimism

1I wrote about it at the time here and here.

2To be fair, Dalio was on the right side of history during the 2008 crisis.